I recently made two new friends: Abhinav Omprakash and Dawn Walker. Abhinav said I’m an optimist and I should write about it. Dawn said I shouldn’t try to coin any new terms. I should know better, but this essay follows Abhinav’s recommendation — and credits Dawn, in the very likely event I should have followed her advice instead.

I have been alive for approximately four decades. Each of those decades was witness to its own fun brand of computering. (And the 2020s, as a bonus.)

- 1980s: Computers! You can have one.

- 1990s: Your computer can talk to every other computer.

- 2000s: Computers can be mainstream. Even fashionable.

- 2010s: The computer’s in your pocket. It yanks programs from the ether.

- 2020s: Ubiquitous Computing happened and I’m not sure anyone even bothered to let Adam Greenfield know.

The big corporations always had access before we, the proletariat. Workstations before PCs, LANs before the Internet, BlackBerry before iPhone. But we always get our grubby little paws on the toys eventually, so there isn’t a meaningful divide between B2B and B2C. Just a minor temporal gap.

Entire libraries have been written on the anticompetitive nature of large tech Microsofts, an Apple’s shoddy hardware designed for obsolescence, some Amazon’s ruthless business practices and exploitation of the open source ecosystem, The Google’s 20-year privacy decay and its utter lack of respect of even its paying customers, Facebook and/or Meta’s direct role in genocide, and the general deterioration of computing products.

It’s been said before. We don’t need to go over all that here.

Let’s instead focus on the valuable output of these companies (and others), what we can take from them, and how it might converge with indie tech in a fun cornucopia of colourful goop.

The Two Things I Don’t Mean

People confuse the things I say a lot. A lot. Somehow, when I started an employee-owned software company back in 2012, people in Bangalore would often confuse it with some sort of arbitrary idealism (“well, that’s a cute idea but I can’t see how it would ever work”) and people in Canada — people who buy their gasoline and groceries from a store named, I shit you not, “The Co-op” — thought I was starting an NGO.

People tend to get equally confused when I talk about open source, the merits of e2ee, the merits of federation and protocols, Right To Repair, democratic corporations, and so on. Perhaps I’m just a poor communicator.

But this confusion might just be the natural tendency we all have to prefer simple binaries, extremes, and ideals. It’s easier to waggle our heads at someone we perceive as an idealist or to point an accusing finger at someone’s extremism than it is to treeshake the nuance.

When it comes to optimism, there are are two extremes I will ask you to put in a box and bury in a deep, dark hole.

First, I do not mean techno-optimism, of any kind. Good god do I not mean this. Not that sort of dystopian extremism advocated by Mr. Ben Andreessen (that sure is a hard name to type… I wonder if it was Andre Essen at one point in his family tree) and certainly not the sort that could be captured in manifestos written in the most exhausting grammar imaginable. (Did you read that thing? Doesn’t Ben Andreessen have $5 billion dollars? You’d think he would have hired a ghostwriter.) But also not whatever Mr. MKBHD Esq. is referring to when he describes a Tesla event populated with pretend humanoid robots as “optimistic”.

This is not the optimism of the technology elite. Whatever I’m talking about, it’s probably not even very sexy.

Second, I do not mean Permacomputing, Solidarity Economy, System Thinking, Systemic Design, Sustainable Computing, Computing Within Limits, or… any of that stuff. Those things are cool and nice and fine but they have a certain taste I’m trying to avoid here. I think that taste is the aftertaste of hard tack and hummus washed down with a Twenty Winds Chai Tea Latte.

This is not the optimism of the hippies or artists. Whatever I’m talking about, it still makes money.

Both of these extremes crave something. It might be another trillion dollars thanks to the latest business gadgetry. It might be a technological answer to society’s fundamentally social problems. It might be an idolized 1980s that never really was. It might be nothing more than a masturbatory and self-indulgent performance.

Real optimism doesn’t really want anything. Rather, it just anticipates a specific inevitability based on the confluence of a bunch of darn great ideas.

Boot To Kill

The first of these great ideas is easily misattributed to the Apple of the mid-2000s: simplicity and ease of use. Sure, they tried their best, too. The 4th generation iPod is still a work of art. But as we all know, the true herald was 1997’s Diablo by Blizzard North. David Brevik describes the key design decision this way:

“Time from boot up to kill was, like … it’s gotta be under a minute.”

I love this quote. From the moment I heard it, I’ve abused it on every product I’ve built since.

So much is bundled into this idea. It Just Works is at home here; you don’t get to give your users a manual or a How-To or a README or a Quickstart. There can’t be a cluster to stand up with 15 lines of boilerplate or just a little glue code or a YAML file to edit if you only have one minute. Setup for systems like this is “push the power button to turn it on.” Bam. You’re there. There’s a ton of social and technical complexity that one must eliminate to do this correctly. Complexity can be limited, I suppose, by squeezing the blubber through a tiny hole like the App Store (which is not a true narrow waist), but it’s always more satisfying when someone treats this idea as fundamental to their product.

There are a bunch of other ideas that come for free with “boot to kill in under a minute”: Limiting (or eliminating) dependencies, simplicity, raw ease of use, less-is-more, and No Login. That last one stands for “Now Optional Login” in the same way NoSQL stands for “Not Only SQL”, I think.

As developers, we all appreciate small, simple, composable things with zero dependencies. But as users? One of the most annoying points of friction in software these days is the seemingly-ubiquitous requirement to Create A New Account To Get Started! for all sorts of software that shouldn’t need one. Taking my email or phone number and sending me an OTP is equivalent to creating an account. You’ve got me now. I don’t want to get got.

There are notable exceptions: Gather Town and the ever-delightful Excalidraw. Gather Town is exclusively social and Excalidraw is only as social as you want it to be, suggesting that many of the apps and team tools we use today don’t really require a login. I sometimes open Excalidraw only to be greeted by my last doodle from months or years prior. I can’t say the same for Microsoft 365, even though it makes me log in 173 times a day. As I scroll through my password manager, only my email provider, bank, and government immigration websites stand out as apps that require some form of identity with the very first use. And maybe Furcadia.

Identity or not, there’s been a great deal of marketing nonsense spewed (spewn? I think spewn.) across our industry claiming one thing or another “delights users.” But delightful products rarely get to bask in the radiance of the user’s euphoria. An excellent product is one we take for granted almost instantly: Install it with one click. It works. It works every time. We quickly start to forget it’s even there.

Most people aren’t delighted when they pour themselves a cup of clean water from the tap. Nor should they be. This should be the default. Good software is a utility — we only notice it when it breaks. And a good utility never breaks.

Less, less, less.

Diablo may have defined the best user experiences of our generation but I will credit Apple with pushing one idea throughout the Intel era: less. Obviously Apple doesn’t want us to buy fewer phones. But MacOS took what was essential in BSDs and gave it to you with fewer options, in the name of fashion. (If you really needed the options, you could dig.) The iPod had few, if any, options. The iPhone limited screen real estate and click precision in a way that forced UI and UX that was just… less.

Giving someone less is also often described as giving them a product which is opinionated, fashionable, or constrained. Maybe that product is an immutable data structure. Maybe that product is Rust or Rails or Flutter. Maybe that product is their entire computer.

What does immutability have in common with NES cartridges? Immutability, whether at the PL level like Rust, at the primary memory level like Clojure, or at the disk level like Kafka (and my own little experiment, Endatabas), eliminates an entire category of complexity by removing power and transparency from the user. NES cartridges, likewise. It’s hard to break a NES game by overwriting a critical file or by upgrading a dependency in a way that isn’t backward-compatible. Power has been taken away from the user and an opinionated experience is provided in return.

I feel your tension. Most of these things are the antithesis of hacker culture! you say. Indeed, the tension isn’t yours alone. The tension is real. It’s very difficult to create a product which encourages your customers to repair it, to tinker with it, or even just to use it in a way they particularly want aaaand provide an opinionated user experience — but it can be done. Of course, most companies will choose one side of this tension or the other. Framework emphasizes RTR. Oxide emphasizes OOTB. But the out-of-the-box Framework experience is still very good and an Oxide computer is still repairable.

Many modern software products attempt to give us less-is-more UX, fashion, and sleek, sexy UIs. Some succeed, some don’t. That list includes software from every corner… those smooth operators like Notion, Figma, Things, Signal, Tailscale, Warp Terminal, GNOME 47, Bluesky, and — for some reason I’ll never quite understand — every JavaScript framework on the planet.

There will never be a perfect answer with which to resolve this tension. Instead, product owners get to use this tension as a playground. How powerful and hackable can a product be while still providing an opinionated user experience with less to worry about? How much do I even care about either of those things? It’s up to you to decide! Yay!

Done.

Speaking of NES cartridges, you may have noticed the resurgence of retrocomputing these days. Everywhere I look, there are folks building for 16-bit platforms, creating pixel art, revisiting the demoscene, writing all sorts of emulators, and digging around for various ancient hardware at estate sales. Powering up an old Amiga or Beeb, popping a floppy, and watching the old beast spring to life is a very specific kind of joy appreciated by a very specific kind of nerd.

But I take issue with an idea I see bandied about as though it were the natural and inevitable coda to that experience: “But, of course, you couldn’t do that TODAY.” (The Permacomputing folks have a different beef with retrocomputing. That’s their beef, not mine.)

Rarely does it take on a medium so concrete as an NES cartridge, but software that is “Done” still exists today. It can still be created today. For many chunky lumps of enterprise software, software must be “Done.” Companies do not have infinite money to spend on Continuous Improvements, ad infinitum. If your bank and your health insurance can run on 40-year-old COBOL, surely a service, built on open standards with well-defined boundaries, could also survive 40 years?

The execuse, of course, is always that a modern program must interact with the Internet, which is big and bad, and that security is hard. So of course software can’t be “Done.”

But this is a cop-out. It is true that network-connected hardware is harder to, uh, harden. It is not true that it cannot be done. And in many cases, software can be stable with only security updates. Entire BSD and Linux distros exist in this middle ground. At worst, a consumer-grade application that was “Done” but stands on top of some library or protocol with a fatal security flaw will simply have to run offline forever.

All your software is offline-capable if need be, right?

Local-First

Even non-programmers are discovering the strange truth that the entire software industry was “tricked into going back to time-sharing”. Thankfully, Martin Kleppmann recently took a crack at distilling “local-first” down from the original 7 Ideals to the far more concise:

The availability of another computer should never prevent you from working.

This rule is just so lovely, in so many ways. First, it actually captures more than the original 7 Ideals, in fewer words. The original 7 Ideals were synonyms of: snappy, multi-device, works offline, collaboration, long now, security and privacy by default, user ownership and control. The difficulty with this list, of course, is that each of these items is subject to interpretation — and a system which adheres to, say, 5 of 7 ideals may still try to stamp itelf with that sweet “LoFi Inside” logo. (Linear, a snappy SaaS kanban board which may not exist by the time you read this and which, in my mind, has nothing to do with lo-fi, is a great example.)

If other computers aren’t allowed to get in my way, then the services those computers represent (or provide, by way of execution) also cannot get in my way. Reliability is baked into this ideal. It Just Works is baked into this ideal. I mean, if It — whatever It happens to be — is not working, presumably you’re prevented from working, too. And that’s the rule we’re not allowed to break in the lo-fi world. Thus, It Works Forever is baked into this ideal. The company that makes your software might deteriorate, change its business model, or disappear entirely… but (any given release of) your software should not. Right To Repair is implied, and so, as a consequence, open source is also implied. (Though neither is a hard requirement.) Longevity is baked in. If aitch tee tee pee linear dot app goes offline, my bloody kanban board todo list thingy better keep working. Forever.

If someone else’s computer isn’t allowed to stop me from working, it’s no longer required to declare that I (or my business) own and control the software I (or my business) run and the data we create — it’s self-evident. As a consequence, sovereignty is strongly implied. I mean, it would still be technically possible for Slack Inc. to siphon off all my company’s data to feed their hungry data mining partner companies if Slack-The-App were local-first by Martin’s definition. It would just be very weird. It feels more obviously wrong for Slack to steal my company’s data if there isn’t even a reason for their product to talk to slack dot com.

It’s strange to think of all the many happy downstream consequences of this one punchy little requirement. It’s exciting to think about an entirely new breed of software that treats their customers — individuals and corporations, both — with this kind of respect.

Every User is a Power User

There’s some strange froth on the horizon of the internet. White caps, even. It’s not nearly as easy to see as the dominance of retrocomputing but that’s because retrocomputing is right here in the boat and the froth is, like, dozens of nautical miles away. I’m not a sailor so I’m not sure if that’s actually far. And I’m quite blind in one eye.

There’s a small contingent of ex-colleagues of mine, including Malcolm Sparks and Jasim Basheer, who are huge proponents of the idea that the user and the developer are artificial categories, that we should and could actively blur the boundary between them. They love old systems like HyperCard and Visual Basic, without the nostalgia that normally accompanies those memories. I don’t think many people can rediscover the magic of VB3, but Maggie Appleton’s “barefoot developers” might bring these old ideas to life in the text editor (or prompt box) first, rather than by drawing a button onto an empty window and double-clicking it to attach an event handler. Say what you might about recent developments in LLMs, even I can write a bash script in 2024. Combining that idea with local-first and putting those tools in more hands will give the average user a leg up. These older ideas of empowering users with programmatic tools have resurfaced any number of times over the years, but however proprietary your VBX objects might have been, your Salesforce Data Model Objects are objectively worse.

Meanwhile, all sorts of cute 1990s ideas have found a home in the minds of 2020s humans. It feels a bit like the GeoCities era. You’ll hear Google employees unironically discuss the Open Web. You’ll hear SaaS salesmen like DHH pitching bare metal and software ownership. It’s getting harder and harder to step into a living room that isn’t running a little homelab or self-hosting an invite-only Mastodon server.

After a heavy decade, filled with this looming feeling like the large cloud vendors might slurp all the juice out of that sweet, sweet LAMP stack fruit with their slippery proboscides, it feels as though perhaps things are turning a corner? These products only live by way of open source, open protocols, open formats, open interop, and (in the case of email) federation. Every goofy little homelab is a tiny defense against your favourite database product getting jeff’d.

There’s a gap between these two. Someone asking ChatGPT to write them a Python script that will download all their YouTube videos from an API and turn it into an Excel workbook probably has very different interests than someone running Navidrome at home so she can listen to her own MP3s instead of paying for Spotify forever. But not so different? It’s easy to see how one day soon, both of these budding hackers could be the same person and she might not label herself a “hacker” at all.

This is one space where consumers get the toys first. I’m not sure how many offices let you run a fileserver or Kafka cluster under your desk… but maybe that time is coming.

Boring Tech, Boring Businesses

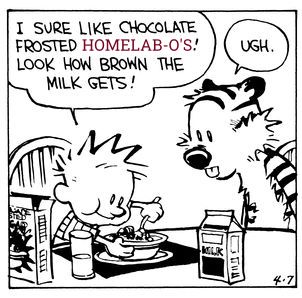

We all respect Boring Technology. But what about the boring businesses? If you weren’t paying attention, you might have read all the above points with some sort of lens that implies they’re idealistic, futuristic, and dreamy. I told you they weren’t from the very beginning, though, remember? This stuff isn’t just for homelabos (which, by the way, I cannot read any other way than “Homelab-O’s”, like the kind of O-shaped breakfast cereal that tastes of chocolate-covered homelab) and developers at Signal Messenger. Or… what’s nerdier than Signal? … SecureScuttleButt? No, that goes too far. But you get the idea.

Okay, so what does any of this have to do with writing software for an insurance company or a real estate company? Well, if the world is tilting toward better behaviour — a world in which companies respect our (and one another’s) privacy and security, a world in which software works even if the manufacturer skips town, a world in which you’re probably paying for services and not the raw, unwashed software itself — then it’s a lot less likely that the insurance company you work for is going to ask you to scrape up all the customer PII and sell it to their partners via an API.

This may seem like a minor thing, but it could be profound! If enshittification (I really don’t like that word, for what it’s worth, but we all know what it means so it carries a certain utility) is one tine of this particular fork in the road then the other isn’t subject to the same kind of decay. The second tine, the better tine, is a mountain of good technology and good ideas, all piled on top of one other. It’s hard to disassemble or degrade the mountain if it’s just too big and heavy to bother with. And the insurance company won’t bother. They’d rather sell insurance.

The Great Convergence

It seems we are on the cusp of a new wave of computing. It will be hard to hype because there isn’t really any value in hyping it… it’s just happening. And it’s not happening at breakneck speed. A world filled with this Really Good Software might happen in the 2030s or it might happen in your grandchildren’s lifetime. Computing is a melting pot of ideas, good and bad. When we build anything with computers, we stir the pot. The thing about ideas which espouse resilience and longevity is that they’re more likely to survive themselves. I really have no idea when we’ll live in such a world — but I do know it’s inevitable.

Most of these ideas are pretty old. This isn’t an optimism born of fairy tales because, truth be told, most of the software we have today is actually… fine? … but applying these ideas would make it so much better. A Google that doesn’t spy on me, beautiful products that will make Tim Apple cry tears of penitence, a cloud computer my company really owns top to bottom, immutable systems that comprehensively obliterate the problem of mutation, open protocols out the wazoo, software I can pass down to my niece and goddaughter, tools that always work and work anywhere, businesses that actually sell something … the list goes on and on. Every little glimpse we get is exciting to me. There’s a lot of fun stuff happening in computers right now.

Of course, no one product, company, or indie project will ever catch hold of all these ideas. Some of them even contradict others, so it’s impossible to tick every box. But the greater the number of good ideas any one company or product chooses to keep in its basket, the more capable staff it can hire (good hackers love to work on good products) and the more savvy customers it will attract. Slowly but surely, everyone else will follow.