Commercial Open Source Software (COSS) is an only-loosely-agreed-upon term for businesses built upon selling open source products. COSS has seen two significant waves pass, with a third now emerging. The head of each wave lasts approximately a decade. The tail of each wave extends into the future indefinitely. Each wave subsumes all previous waves.

The first wave was characterized by shrinkwrapping and commercial support. Peaking in the mid-1990s, Red Hat was the poster-child of selling support for software written by other people. On the surface, the literal shrinkwrapping is what many of us remember from this time period: graphical installers, Linux on CD, and RPMs built by paid employees. While branding and polish isn’t to be underplayed, it was support the enterprise wanted — and bought.

The second wave was characterized by Open Core products and, occasionally, dual-licensing. The term “Open Core” is harder to define than “Commercial Open Source”. There exist obvious examples of true open source cores to otherwise proprietary software products: GitLab, Mattermost, and Metabase provide the classic Community Edition vs. Enterprise Edition dichotomy. Other businesses are harder to categorize. Many products — including Telegram, Keybase, and Canonical Snap Store — release open source clients to proprietary services and don’t qualify as commercial open source at all.

MySQL was one of the first products to employ dual licensing, capitalizing on the restrictive nature of the GPL. Dual licensing was a huge component of their 186-page 2013 pitch deck. MySQL, while undoubtedly second-wave, wasn’t Open Core.

The third wave is weirder than both these previous waves. For one, most of the world now readily accepts that open source projects must be financially sustainable. There still exist beloved projects like VLC, which refuse ad funding and venture capital, on principle. But most open source projects are increasingly moving toward a revenue model of some kind. The third wave embraces financial stability with new tools, in addition to the old strategies of shrink-wrapping and open core. Jamie Brandon has coined the term “over-the-wall open source”, which refers to the idea that the traditional aspects of an open source project — a public issue tracker, a public code repository, a mailing list, a chatroom, and so on — are optional. If I build a video editing tool for iOS behind closed doors but release a tarball of the source under an open source license with every (paid) binary release, that’s still open source. Rich Hickey’s Open Source is Not About You points directly at this underlying truth of open source:

Open source is a licensing and delivery mechanism, period.

Just because it is common to build open source in public does not mean community or social engagement or the entitlement of users have anything to do with it. And removing some of those things creates a revenue opportunity. Want a specific feature built into the product? As a team of 3, we’ll build it over 2 months for $150,000. Does your company want read-only access to the issue tracker? $50/mo. Does your company want read-write access to the issue tracker? $150/mo. Or whatever. The idea that open source is somehow synonymous with martyrdom, the selfless service of a public library, or 24/7 transparency is an understandable error, but an error nonetheless.

What Open Source Is Not

A few years ago, I actually had a colleague state that “no one decides what ‘open source’ means — not the FSF, not the Open Source Initiative, not Debian’s DFSG, nobody.” I didn’t bother pointing out the existence of The Open Source Definition, or the fact that the OSI coined the term … or the fact that it’s incredibly helpful for words to mean things. I just took a moment to absorb the absurdity of the comment, and how clearly it demonstrated that we’d gone off the rails as an industry. This particular fellow was old enough to remember the birth of these concepts, experienced enough to have employed them, and wise enough that he should have known better.

Licenses which are More Open Source Than Open Source, like the SSPL, are not open source. These licenses have been considered by the governing bodies which help guide our collective understanding. And they’ve been rejected.

Licenses which are Not Really Licenses, like the

BUSL

(pronounced “boozle”),

are not open source.

These are license templates, which really do not need to exist in the contents of LICENSE, at all.

The timebomb of lemony fresh scent that’s released when the BUSL change date is activated might as well just be located in a specific file for that purpose: PROMISE, LICENSE-TIMEBOMB, or something.

Not only are these projects not open source, but they don’t even provide a consistent license in the way the SSPL does.

Your company can ask your lawyers to certify the SSPL safe to use.

Your company cannot certify the BUSL safe to use, because it changes with every product it applies to.

Licenses Attempting To Take The Law Into Their Own Hands are not open source. The Hippocratic License and RAIL are examples of this, but it seems like there’s a new one every month. (This isn’t to say these aren’t admirable attempts to solve a very real problem. But as far as open source is concerned, they don’t solve the problem in a way that’s backwards-compatible. Back issues of Luis Villa’s Open(ish) Machine Learning News are probably the best place to get real insight into this struggle, from a real lawyer.)

Third Wave Open Source does not include these fad licenses or license templates. Instead, they sit on the fringe, looking in.

The Ultra Third Wave License

Most open source products I’ve heard people identify as third wave use the AGPL-3.0. Why? Permissive licenses eventually cause rot. It took 24 years, but in 2023, MacOS Darwin closed the doors on its BSD-licensed origins. And as attorney Martin Clausen puts it, there are three kinds of Copyleft: Weak, Strong, and Ultra. Currently, the AGPL-3.0 is the only license which falls in this third category, ensuring that the rights of users cannot be stripped simply by providing software over-the-wire. As Evan Czaplicki stated in The Economics of Programming Languages (a talk which applies to other forms of software products as well), all software creators want to prevent “getting Jeff’d”. It’s not entirely possible to avoid getting Jeff’d, because open source can’t discriminate against anyone (even Jeff), but the AGPL-3.0 is a good start.

Communal Altruism? Or Centralized Capitalism?

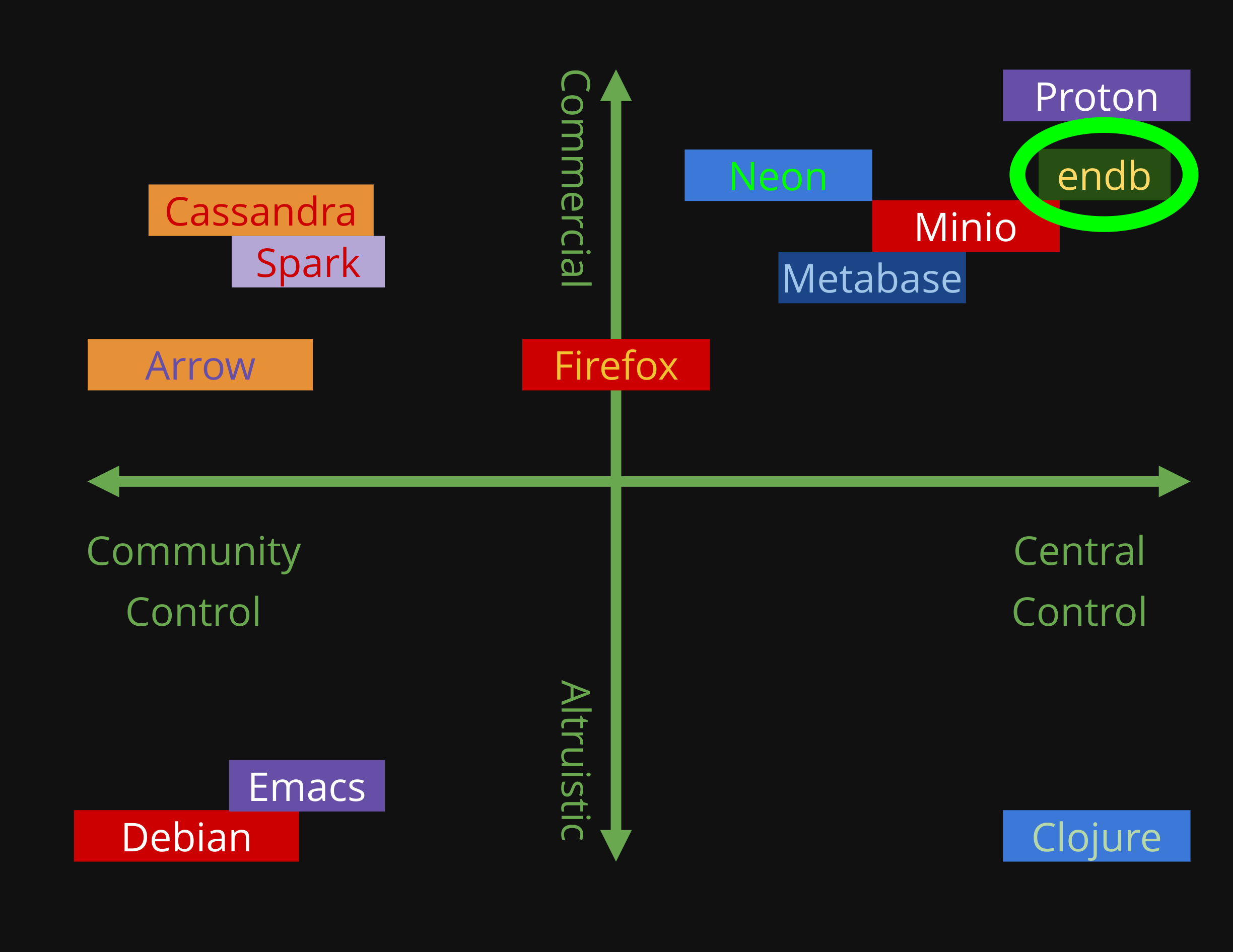

Por que no los dos? There isn’t one best way to build and run an open source product. The approaches of Debian, Clojure, Proton Mail, Firefox, and Apache Cassandra are all wildly different. And they all work in different ways.

This diagram places a few sample projects on a plane, but you can probably guess which quadrant I’m placing my bets on: commercial delivery and centralized control. It’s hard to build a company out of a rag-tag group of developers, scattered throughout the globe, who only know each other from the types of jokes they tell on IRC. It’s also hard to build software without money. Even the examples in the “Altruistic” category were financed, somehow. Perens, Stallman, and Hickey all made money from consulting gigs. DHH made money from products associated with Rails. Some Debian maintainers are paid by universities.

Centralizing control doesn’t eliminate community and the license protects the (somewhat) altruistic nature inherent to open source software. When a leader dies, retires, or decides to burn bridges, the healthiest projects will still witness succession, either in the form of a new BDFL or a fork. But centralization brings other advantages.

The Firefox Phenomenon

Back in 2018, I co-authored an article on the advent of clean design with Varun Pai, our lead designer at Nilenso Software: Designing for Open Source Software. While this article finishes with a focus on our specific design choices, the crux of the article is as valid today as it was half a decade ago: good design is essential. A coherent, centralized, full-time team helps a great deal when building good design.

In 2006, Firefox’s heyday, “good design” was a lot easier to point to. No ugly ads. Clean interfaces. Snappy response times. A brand so loved by fans they cut a crop circle visible on Google Earth (for a while).

20 years later, Firefox is coughing up its death hairball — but all these qualities are now taken for granted. Users still hate slow, buggy, laggy, and messy software. But we’ve also grown to demand more of the companies we buy software from, as they increasingly violate the privacy of individuals and companies, exploit copyrighted material, and sell influence. Good design in 2024 respects users’ autonomy, an ironic ouroboros of open source principles now defining quality design, in the abstract. If we time-travel back to the birth of today’s Computer Science Masters students, “open source” was synonymous with designs as hideous as the Gnutella config screen.

But there was another design event which framed what quality design means today: the iPhone. Apple played no small part in elevating discourse surrounding the software design discipline throughout the 21st century. The iPhone (and small touchscreens, in general) played the specific part of transforming simplicity and ease-of-use into salient features for new products: push a button to call a cab, open a map that tells you where you are, record a patient’s blood pressure, check your bank balance with your fingerprint, learn a new language while you wait for the bus, edit your company’s website with a few clicks.

Simplicity is a requirement for third wave open source and the space that surrounds it. VLC just works. Linux on a Framework laptop just works. Plausible Analytics just works. Signal just works.

All these products benefit from centralized control of the product vision and the user experience that follows from that. But, as users, we don’t just want another pendulum swing back into the SaaS product hell that brought us Our Incredible Journey and killedbygoogle.com. Even though central control builds a better product, it paradoxically can’t be trusted to maintain that product indefinitely. We need to hedge our bets.

Local-First

I’d argue that the principles of local-first software (succinctly captured by Martin Kleppmann: “The availability of another computer should never prevent you from working.”) are about to become the new ideals of open source software. Yes, software must be beautiful and efficient and respect your privacy. But it should also keep working even when the manufacturer goes out of business.

This isn’t to say that all third wave open source must be local-first. But if your software actively violates these principles — because it doesn’t work without a network connection, or because it relies entirely on a service the user doesn’t control (whether free or paid), or because it makes data opaque to users, or because doesn’t allow users to control their data, or because it violates privacy, or because it makes data ephemeral — the less likely it is to qualify for the title of Third Wave Open Source.

Third wave open source is future-focused, and local-first software isn’t just a prescient idea — it’s an inevitability.

Examples

There are plenty of examples of third wave open source, including those mentioned above.

Framework Computer and Oxide Computer are perhaps the more confusing entries, because they have the peculiarity of being hardware products. However, Framework makes running Linux (an open source product from the beginning of the era) effortless and embodies the principles of third wave open source: it gives power and control to the user by enabling the Right To Repair. Oxide releases all their software as open source, as far as I’m aware.

Some third wave open source companies produce copycat products: cal.com, Bitwarden, Typesense, Neon, Minio, Plausible, Nextcloud, Element (Matrix), Supabase, and Proton all fit under this label. This isn’t an accusation. Being open source is a perfectly valid differentiator.

Others, like Metabase, embrace open core. Excalidraw and other login-less web apps embrace instant startup. Atuin bridges a hardcore command line utility and a SaaS business. A parade of Mastodon clients have replaced the charm of Twitter clients from yesteryear.

Whatever the model, these tools are giving power back to users and embracing the original intent of open source, in contrast to companies that slap a GitHub logo on their website, linking to a few clients or drivers they’ve open-sourced for their otherwise closed data, product, or platform.

The Future

Personally, it’s hard for me to imagine working for a company which doesn’t produce third wave open source. I could quite happily work for most of the companies mentioned above.

And there are tons of applications that don’t have competitive open source equivalents yet:

- collaborative documents (word processing, spreadsheets)

- cloud computing

- joyful note-taking

- project management

- corporate chat (Teams, Slack)

- video chat (Zoom, Meet)

- recipes

- photo sharing (Instagram)

- classifieds (Facebook Marketplace, Craigslist, Kijiji)

- CAD

- video editing

- audio editing

- phones

- exercise trackers

- workout equipment

- newspapers

- desktop publishing

- music

- TV, movies

The list could go on forever. I look forward to replacing my day-to-day apps as companies put out new open source products in all these categories.