Can I interest you in a nutrition label?

Ethics! We all have a few.

Every day, my personal ethics evolve in varying degrees. It seemed harmless to speak loudly and abrasively in my early twenties — a speech full of arbitrary and contrary words. Who was I hurting? Now I know. The increments of personal ethics evolution are slow and sometimes the work takes decades. Crossing the bridge of intoxicants, for example. On one side, a world in which I saw no harm in smoking, drinking, and encouraging others to do the same. On the other, a dark shadow of the former world: a decade spent on the far side of the earth waiting to return to the people I smoked and drank with in 2006. A decade is enough time to see both the damage and the role I played in setting it up.

Everyone will have a different set of ethics governing their opinions about topics as varied as space travel, immigration, social programs, and personal product consumption. But while most of us can only wax poetic about space travel or write angry Facebook posts about our temporary government’s temporary immigration policy, we all have nearly consummate autonomy over the behaviours we engage in and the products we buy. And in this world of individual ethics, we all tend to prefer a manageable world — a world simplified and distilled into categories we can use as meaningful approximations of our true feelings. We may choose some rough trajectories: I’d like to eat less meat. I won’t buy clothes just for the sake of buying clothes. But the approximations we like best are the specific ones we can point to and say I am/do/buy this thing. I am vegan. I ride a bicycle. I buy GMO food.

Labels are helpful. They are a tool, a means of avoiding the untenable situation wherein we rebuild our ethics from first principles every single day.

Software Ethics: How deep is the rabbit hole?

As it turns out… pretty deep. And for most people, that depth is beyond meaningless. Even those of us who really enjoy software licensing discussions eventually get numb to the idea of filing off the edges from one more debate on ethics and legalities, largely mired in nerd-porn semantics and contexts which are impossible to faithfully reconstruct. In response to my essay on the topic (Software Ethics), even the nerdiest of my friends told me it was too long and too detailed. The difficulty is one of specificity. What does it mean for software to be “federated”? What are the nuances between “free software” and “open source”? What are the differences between the GPLv3 and the AGPLv3? And who cares?

Most people don’t care and they shouldn’t have to. But even for those of us who actually love this stuff, it would be nice to segregate the conversation. There is a world of difference between discussing your GMO preferences with your family and buying (or avoiding) GMO products at the store. That difference doesn’t really exist for the world of software ethics at the moment.

What kind of labels could we employ in the landscape of software ethics? How specific should they be?

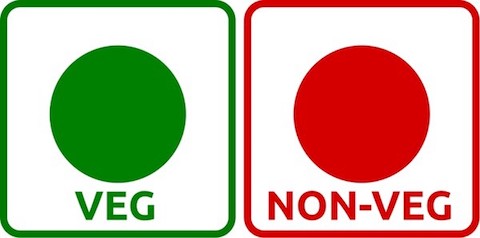

Veg / Non-veg: Simple, Universal, Reproducible

There are many things to love about India but the veg/non-veg iconography is easily in my top ten, where design is concerned. What I love about it, in part, is that I have no idea where it came from. It was mandated in 2006 but has been around for much longer than that. The icons couldn’t be simpler (caveat: they’re actually a little too simple, as we’ll see). They are universally understood across India. And they are very easy to reproduce. Reproductions are often inconsistent: shapes and colours are slightly distorted, words are added. These mutations don’t seem to matter because the essence is always understood.

The failure of the veg/non-veg icons is, of course, their structure. Red/green colour blindness is common and differentiating by colour alone is a substantial iconographic mistake. The design principles can be borrowed though. Can we come up with labels for software ethics which are simple, universal, and reproducible?

What kinds of software do we need to label?

For the most part, software today follows a sufficiently standard format. It’s likely that I’m going to lose some people here, but I would argue that almost all software these days is a client-server architecture of some sort and that, although the advent of ubiquitous computing hasn’t quite happened yet, we are definitely progressing toward ubiquitous computing. That means that users have to start caring about this client-server architecture. Sorry. In the context of a conversation about software ethics, client-server can be replaced with the contemporary lingo of app-service and we’re still on the same page. (Where app is short for either application or appliance.)

Some quick counterexamples and defences: Operating systems? Where are the updates coming from? Microsoft, Google, Apple, RedHat, and Canonical are your service providers. Roomba firmware? If iRobot isn’t sending you over-the-air updates, they soon will be. Cryptocurrencies? P2P is the very definition of the federation endgame.

If all software is a variation of app-service, then all software has to answer to these three static, ethical queries: Are you Free? Are you encrypted? Are you federated? It is up to you to decide which of these axes define meaningful software ethics for you. Your ethics are yours. But wouldn’t it be nice if someone put a label on the box so you knew what was inside?

The Grid: Alpha v0.1

To review, we first want some extremely simple, (potentially) universal, easily reproducible labels. These labels should be easy to recognize at a glance, even when they are reduced to black-and-white, which means we must make them identifiable by shape in addition to colour. Optionally, they could include text in any language. Secondly, they should tell us this at-a-glance information about the three axes of software ethics: Encrypted? Free? Federated?

Let’s give it a try.

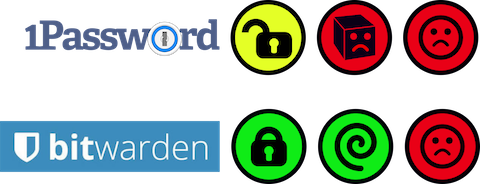

Software Ethics nutritional labels for you and your family. ❤

Software Ethics nutritional labels for you and your family. ❤

Similar to seeing veg/non-veg icons for the first time, these icons might not be immediately obvious. Let’s break them down:

The encryption row is probably the least ambiguous I could manage. Red sadface open lock? That’s no encryption. Yellow open lock? That’s weak encryption. The three yellow categories are both the hardest to define and the most flexible. Weak encryption could mean many things. Maybe the encryption isn’t end-to-end. Maybe it is only available on certain channels. Maybe the code can’t be audited because it’s completely closed-source. A green lock is strong, end-to-end encryption that’s always on and completely under your control. You’re not getting a green encryption label with a red Freedom label, obviously.

The freedom row gets progressively ambiguous as a software’s status improves. (Given that most software we use won’t qualify for a green badge any time soon, maybe that’s fine?) A sadface black box swimming in a red circle is proprietary, closed-source software. A yellow OSI logo is open source, with all the usual caveats attached to that term. Maybe the company that builds this software sells closed or proprietary upgrades? Maybe some of their features are hidden behind black-box services? A green swirl is Free Software that you can self-host. The green swirl is a bastardization of the Debian logo because the Debian Free Software Guidelines have an inherent network effect that software licenses applied to individual pieces of software do not. The swirl is also kind of an extension of the OSI logo, which is sort of… half a swirl? I’m obviously open to better ideas here. There’s always some confusion about self-hosting. The requirement that software can be self-hosted has nothing to do with actually performing a self-host. The fact that users can self-host means that anyone can self-host and that users will never be forcibly dependent on one government, agency, or vendor. PS: If freedom row leaves a bad taste in your mouth, swap it out for audit row. Close enough.

The federation row is, in some ways, the simplest. But as most people I talk to about this are very confused as to what federation is exactly, let’s draw our lines in the sand. A red sadface circle-in-a-circle is a centralized service. A service may be free/open, easy to self-host, and fully encrypted but it can still fail this test very easily. Centralization is best defined in terms of what it is not: A yellow federation label with two connected service bubbles (that’s what those circles are) means that services can share data over a federated protocol. If a service does not do this, it is not federated at all and gets a red label. And if the lines between service and app (or server and client) begin to blur, we’d apply a green label with three service bubbles (and no little client dots). This is the world of peer-to-peer federation protocols: most blockchain implementations, Gnutella, and kin.

Text-only Alternatives?

My friend Arun suggested that Creative Commons-style text labels would be useful as a shorthand. Similar to the BY-NC-SA labeling, we could have Not Encrypted, Weakly Encrypted, Strongly Encrypted; No Source, Open Source, Free Software; No Federation, Service Federation, Peer Federation:

NE|WE|SE — NS|OS|FS — NF|SF|PF

Looking at modern password managers, for example, Bitwarden is SE-FS-NF, KeePassX is SE-FS-NF, and 1Password is WE-NS-NF.

If we wanted to get obsessive about symmetry, we might be tempted to try Not Encrypted, Weakly Encrypted, Fully Encrypted; No Source, Weak Source, Free Software, No Federation, Weakly Federated, Fully Federated:

NE|WE|FE — NS|WS|FS — NF|WF|FF

Preferred naming convention? Cast your vote by mailing me a cheque.

Let’s label some software!

If every piece of software came with these labels, you would still need to decide which matter to you — and when. Just as we don’t attempt to max out the number of labels on our food, the goal here is not to limit yourself to software that gets three green badges. In 2019, it’s pretty unlikely that any of us want a federated password manager and so a good password manager probably gets labels like the ones we saw for Bitwarden and KeePassX. 1Password, on the other hand, rates a D-minus in software ethics. In full colour, the ratings for 1Password and Bitwarden look like this:

Remember that 1Password can’t even get a green badge for encryption (which they claim to be very good at) unless we can audit their code.

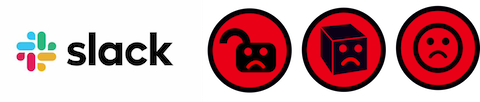

Let’s take a brief look at Slack?

Mom won’t be happy with that report card. Moving on. This article is on Medium. What is Medium’s ethics score?

Ugh. Okay. How about we choose a piece of software that actually earns some clean grades?

Sigh. If only Signal was actually enjoyable to use, we’d be making some progress here. But it isn’t. Signal is a chore. This brings us to another comment Arun made on this whole idea: wouldn’t it be nice if we could somehow capture a software’s health?

Coda

Software ethics isn’t enough. Despite the fact that most of the software we use every day struggles to even find its way onto the ethics spectrum, we simultaneously need to open up the conversation on ethics (with tools like the nutrition label) while moving beyond ethics to include other aspects of software as well.

A software’s health could be measured across any number of variables. How many active users does the software have? How many for the service? How many for the app? How many active servers exist in the federated network? How many actively maintained clients exist in the federated and peer-to-peer scenarios? How many commits-over-time are the developers making? How many of those commits are feature-building commits and how many are security-hardening commits? What is the system’s code complexity by objective metrics? What is the overall lifetime of the system? Does the UX suck? Did it suck yesterday? Is it getting better or worse?

The difficulty with all these measurements, of course, is their purely organic nature. They will all change day to day and can’t be stamped on a box, a homepage, or a Wired article. Measuring software’s health demands a real-time metrics dashboard… which means it’s beyond my pay grade. But I would love to see such a system emerge in the future.

In the meantime, enjoy these Software Ethics Nutritional Labels for evaluating the technology around you. Remix them, try them out for yourself, and tell me where they fail so they can be improved. I hope someone finds them beneficial.

Appendix

- The badge SVG can be found here: https://github.com/deobald/siggu.org/raw/master/article-content/software-ethics-badges/badges-v2.svg

- The draft SVGs and other images can be found here: https://github.com/deobald/siggu.org/tree/master/article-content/software-ethics-badges

- According to this labeling scheme, Bitwarden and KeePassX are not equivalently networked but they are equivalently federated. Did I mention that these conversations can quickly devolve into nerd semantics?

- Nirbheek pointed out that the official status of the veg/non-veg symbols in India require that they are green and brown, not red. I think I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen a brown dot in a brown square, but the mandatory labels defined by the Food Safety and Standards (Packaging and Labelling) laws of 2006/2011 are not actually the ones I’m referring to in the Veg / Non-veg section. Much more interesting, in the context of this discussion, are the implicit simple symbols which were universal because of their ease of reproduction long before the laws ever came into effect.

Essay originally published on medium.com/@deobald (2019).