The inevitable advent of जादूगरों का गाँव.

“Land in Canada costs how much?” Ragul queries me a second time. His eyes are wide and I can tell he’s asking me to confirm the cost of property in Eastern Canada because half of him doesn’t believe it.

“Yeah, I know,” I say, “$23,000 CAD for 20–30 acres is…” I pull out my phone and start punching the forex conversion into the search box but he gives me the answer off the top of his head before I can finish.

“Twelve lakhs. That’s only twelve lakhs. For twenty. acres. of. land. You know in India that will buy you 2000 square feet? Square feet! Maybe it will buy you one acre on some remote mountainside.”

I feel the need to backpedal a little, as if I otherwise run the risk of selling magic beans. “There’s no road, though. And no electricity or water service. It’s just a forest by the ocean. And not all Canadian provinces are that cheap.” But I could tell he was already sold on the idea, just as I was a decade earlier when I bought that little piece of Nova Scotian forest with some friends. The Hacker Ethos finds gravity not in immediate value but in potential value and large, undeveloped plots of land are nothing but. An empty plot of land, a blank canvas, or a system which exists only on a whiteboard — they all whisper maybe this could work into the ears of prospective creators.

The site of our Hacker Village in Canada

The site of our Hacker Village in Canada

We’ve come to Pondicherry for the weekend. We’re living 100 kilometres away in Mahabalipuram, a little temple town which nearly splits the distance between Pondicherry and Chennai. Pondi is a strange place. A French colony which only received its official independence in 1962, it is already full of vocabulary and architecture unlike anything you’ll find in the rest of India — or the rest of France. Add to this unique Tamil-French mashup the buildings of Sri Aurobindo (or the corporation which adopts his logos, I suppose) which regularly punctuate the streets, acting as a constant reminder of the nearby experimental township of Auroville, and you’re unlikely to forget that you are visiting a peculiar city indeed.

But we’re not visiting Pondicherry to drink French coffee and gawk at The Golden Golfball Temple. We’re just stalking rental properties like regular schmucks and our host happens to be Ragul, a member of the Maitri Collective. When I told him we were coming to Pondicherry he insisted that Maitri host us and we happily accepted. It’s a Saturday and half a dozen people end up crashing on the floor of the Maitri building in central Pondicherry. Before we make our beds in the outer hall, an artist collective uses the inner hall as a space for a sketch class. Furniture is modest at Maitri but the inner hall has bookshelves stacked to the ceiling. The sketch class resumes Sunday morning, following the weekly meeting of the local Free Software chapter. We chat well past midnight about books, Vipassana, bootstrapped software, off-grid, and mesh networks. The next day we meet Maitri members whose current project is researching and digitizing ancient Tamil mathematics literature. It’s as if we’ve found the secret guild of art and technology in Pondicherry. A tiny hacker paradise.

Yes. This golden golfball.

Yes. This golden golfball.

I’ve been bouncing the idea around in my head for years now: a Hacker Village. Since the Maitri Collective is a rough microcosm of this idea, I thought I’d try running the idea past Ragul. It’s not an easy idea to convey, of course. Hacker Village has so many connotations — connotations I’d like to avoid. जादूगरों का गाँव (Wizard Village) is probably helpful terminology for many people but it’s not better for an idea to smack of robes and magic wands than electronica and DIY… just different. Hacker usually implies computer experts and, at worst, the limiting world of computer security experts. The word has developed a broader meaning, though. For a while, O’Reilly Media and Make: Magazine tried to construct a convincing replacement in Maker, but that word is so vague as to be almost meaningless. Rather than stretching the word hacker until it loses all value, we can mix it with a word like wizard to give it a dash of silliness and a pinch of mystery. The more images we add to the aggregate picture, the more perspectives we get, and the clearer that picture becomes.

But Ragul doesn’t require this expounding of terms. He gets it immediately. He’s been bouncing this same idea around in his head for years and has even scoped out a potential location near the Kalrayan Hills to start his own hacker village. It becomes clear as we talk that this idea isn’t our own. The idea has a core, a foundation, which is itself emergent. Since I’m not the creator of this foundation — no one is — I’ll undoubtedly get some details wrong. Consider this essay an early RFC.

Abstract

The idea of escaping traffic, smog, noise, and concrete seems to repeatedly surface in spheres I witness, in the flesh and on the web. There is no single motivating factor and there is no single solution. Some people just want a tree or two in their front yard. Some are exasperated by the marketing machine gun, pointed squarely at our metro areas: buy this watch, drink this beer! Many of us, especially in India, are literally choking on air that is more dust than oxygen.

The great cities of the world all have something special to offer. The bicycles of Copenhagen, the discourse of Kolkata, the love of San Francisco, the convenience of Bangalore. This essay contends that building a city is no longer the gargantuan task it once was. Though still an organic process, growing a new city can now begin with clear intentions: zero waste, zero pollution, plenty of flora, high value public spaces, and accommodating private spaces. The new city won’t be an unrealistic utopia. It will simply start with the best the modern world has to offer. As a bonus, you won’t need to take a metro (or cab or bike) ride covering multiple kilometres to see your best friend. They will probably live down the street.

The tools of the villagers

A Hacker Village, née Wizard Village, demands precisely the sort of magic with which our generation has been blessed. Computation, the foremost magic of the 21st century, is cheap and easy to perform. The recent advent of pocket computing (differentiated from personal computing, which for some recondite reason was doomed to categorize only desktop computers of the home) and the inevitability of near-term ubiquitous computing have forced our species’ hand on a few fronts. We don’t like software or hardware that is badly designed. “Complex” is nearly synonymous with “bad” in this context. Everyone is, consciously or not, increasingly aware that the best technology is that which has no user interface at all. Second-best is technology with almost no user interface. We have learned this before with indoor plumbing and electricity. When you turn on the tap and potable water comes out, the system is working. When anything else happens, the system is broken. Infrastructure and its interfaces are best when they are invisible. The only infrastructure we notice is the infrastructure which is either dying or suffering an adolescent growth spurt. (I will postscript, of course, that there are sinks on this planet which attempt to predict when you want water and when you don’t and that I have personally never seen one of these work. A tap is the bare minimum of the Water User Interface and hopefully always will be. Telling the machine when we require its services should always be up to us.) The technology of the hacker village will be simple and useful. Although the hacker village will be technology-heavy, it’s unlikely to be a “smart city” for the same reason it won’t have any “smart” water taps. I hope.

Paradoxically, the magic of physical utility infrastructure is more difficult to come by in the hacker village. There is a reason for this. The hacker village isn’t a Gandhian commune, setting about the task of locally regressing society back a century and building everything from scratch. Plastics and computers are hard to come by and hacker villages will need those. The village will get its computers from China just like you did. If a hacker village grows into a city one day it might build these things for itself but at the apex of humanity’s interconnectedness it’s downright childish to pull a city up by its bootstraps. Computers are easy to import from China and move around. Sewers and roads are difficult. The magic of modern physical utility infrastructure is that it can happen very quickly. Singapore, with unbelievable before-and-after photos of its skyline spanning only a single decade, is the poster child for the accelerating pace of public infrastructure. But you can see it in many cities under active development.

It is here that the Hacker Ethos and global telecommunications unite to bring us the present wave of New Grid experimentation. “Experimentation” means that no one is getting it right. If someone had really figured out this New Grid thing, off-grid, micro-grid, and smart-grid would all be products you could order off of Amazon. They’re not. The off-gridders and micro-gridders of today are the Steve Wozniaks of yesteryear, puttering around with the next big thing because it’s cool and fun. But the shrink-wrapped off-grid setup you buy from Amazon and it’s jumbo cousin, the micro-grid (which might power our hacker villages), are definitely coming. Community-sized electricity storage, whether that takes the form of a battery the size of a shipping container, molten salt, or water pumped underground at high pressure, are under development in almost every country. Power sources like solar panels and wind turbines are already off-the-shelf.

Clean water and sewer systems already exist in micro-grid and off-grid sizes, courtesy waste stabilization ponds and septic fields. So that’s handy.

From tools, a prototype

The final blessing bestowed upon our era is the very notion of “done.” Previous generations have fought to get more, to have more, because it was unclear if there was more to have or not. And it’s always worth trying, right? But thanks to Hans Rosling and The World Bank, we now have a system (Dollar Street) which describes when we’ve made it — as a household, village, or nationstate. Is your house a comfortable temperature, clean and unpolluted, with 24/7 utilities (water, gas, electricity, internet), a toilet, a stove, a fridge, a washing machine, and hot water to bathe? Congratulations! That’s basically it. You are “Level 4” and the scale doesn’t go any higher than that. Growth will always continue toward Level 4, generation after generation, but growth beyond Level 4 represents little more than greed and waste, since the returns quickly diminish.

For this reason, I have come to think of the infrastructure supporting a Level 4 house as a Minimum House. Once you own a Minimum House you aren’t left wanting for anything and you are free to get on with the more meaningful work of a human life: learning, exploring, building, and helping others. Examples of the Minimum House abound: Singapore government housing (which houses 80% of its population, no less), University residences for staff, and the more extreme example of the British iKozie Micro Home. House a village in less than Minimum Housing and you will see the citizens invest their time, energy, and money acquiring precisely that — Minimum Houses — rather than building something interesting. This is why the Minimum House is the starting point for a hacker village, where everyone is hellbent on building something interesting. An eco village of mud huts and tents won’t cut it.

The blueprint hacker village now has a goal and a path to achieve that goal: Minimum (Level 4) Houses and the cleanest infrastructure to create them. Every aspect of the path mentioned so far is limited to the material, though. We will require something immaterial to bind them.

Who are these hackers, anyway?

The Maitri Collective is a microcosm of the hacker village not because of infrastructure. Quite the opposite. Maitri uses their space to the absolute maximum. It is a microcosm because the Maitri ethos is the Hacker Ethos.

The Hacker Ethos, as defined by Steven Levy, has seen modernization since he transcribed it, Aṣṭādhyāyī-style, in 1984. But the core remains: Access to anything which might teach you something about the way the world works should be unlimited and total. All information must be free. Promote decentralization. And perhaps most importantly:

The MIT group defined a hack as a project undertaken or a product built to fulfill some constructive goal but also out of pleasure for mere involvement.

These rules carry corollaries. Where better to begin learning about how the world works than in your own home, using your own home as the textbook? “Where does the water come from? Where does my garbage go? What happens when the toilet flushes? How many kilowatt-hours did I consume today? How do I build it myself?” — these are the questions of the curious off-gridder, the hacker of houses. If all information must be free then it should be easy to learn the answers to these questions. And if we promote decentralization it makes sense for as many people as possible to learn the answers. Once many of us know the answers both intellectually and experientially, by reading and sharing and building our own infrastructure, we must follow the project to its logical conclusion: Don’t Repeat Yourself.

The Hacker Village won’t have any interest in hazing new citizens with a right of passage. Thus, when you arrive in 2030 the mayor won’t hand you a PDF printout of how_to_build_a_house.tex from 2019 and then leave you to your own devices. The intoxicating quality of hacker collectives like Maitri is the shared desire to do something cool. Let’s learn to paint, let’s research materials for electrical turbines, let’s map the city using open tools, let’s build a waiter robot! Doing something cool usually means doing something original. Building the same Minimum House, ad nauseam, clearly isn’t part of that game. Replication is the natural consequence of the Hacker Ethos. First you learn, explore, and research; then you experiment; then you build; finally, you iterate.

Iteration. The last step of Project A becomes the first step of Project B. Whether constructing a Minimum House, digging the village well, putting up point-to-point telecommunications, or buying books to stock the public library, we will want to replicate the project in the future. Doing so should be cheap and simple — or at least cheaper and simpler than it was the last time. As a consequence, after a dozen iterations perhaps, living on Level 4 in a Hacker Village should not require $1000/mo (PPP) in expenditures. Level 4 in a Hacker Village will ultimately be defined by standard of living, not superficial economics.

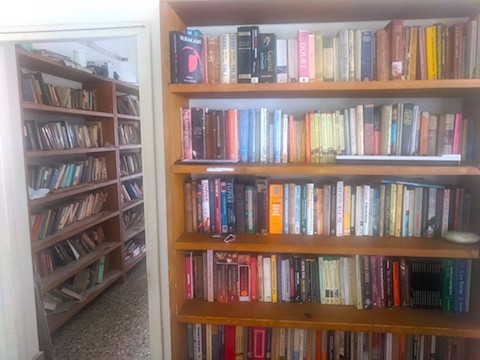

The library at Maitri Collective

The library at Maitri Collective

The Village will borrow other characteristics which shine brightly from hacker collectives: safety, inclusiveness, and a love of literature. We enjoyed the company of people of all stripes during our two brief days in Pondicherry. While modern corporations struggle to understand inclusiveness before etching it into employee handbooks, members of Maitri are just that — friendly, in the most unassuming of ways — and the idea of including people of any sex, age, race, caste, creed, or political leaning is felt, not read. (Maitri means friendship in any number of Indic languages.)

Perhaps Maitri Village is a good image to add to the existing Wizard-Village-plus-Hacker-Village amalgam. It is very likely that the first communal building to go up in the Maitri Village will be a Palace for the People: a public library. It is not hard to imagine Eric Klinenberg’s other social infrastructure examples popping up shortly after: parks, schools, gyms, open universities, tea houses and coffee shops. I also hope that a Silent Space would appear early in the development of the village, whether a Vipassana Centre was nearby or not.

Don’t step in the leadership

Let’s pause for a minute to examine my dig at modern corporations because adding friendship to wizardry and hacking only amplifies some of our already burdensome connotations. To dissolve some of these connotations, it is informative to describe the village in terms of what it is not. The village isn’t an escape from society, governments, globalization, or capitalism. Whether you, a citizen of the village, love these things or hate them is irrelevant. This is the world you live in. Imagining you are starting from a different square on the board is wishful thinking and wishful thinking is a waste of time, a distraction from actually getting things accomplished.

This means there are going to be corporations in the village, big or small. There will be politics, internal and external. There will be import and export (of knowledge, if nothing else). The village will not be a hippie commune, a resort, or a sanctuary for early retirement. If the village is healthy, it will grow through the adolescence of township into adulthood: a city. If the village is unhealthy it will die.

Because cities of the future will require different kinds of corporations and different kinds of politics to survive, it is safe to assume the village will start with different kinds of corporations and different kinds of politics. Cooperatives, tech unions, federations, and neighbourhood parliaments based on Sociocracy are some good examples but many of the future incorporated entity templates don’t even exist yet. The bylaws of the village will be unfamiliar. For example, internal combustion engines and open fires are likely to be illegal. In the near future, human-operated vehicles will probably be illegal, too. The village won’t be anarchy; it will instead try to codify inevitable laws ahead of the curve. Ragul suggested we capture this with வழிகாட்டி கிராமம் (Village of Guides), adding one more limb to our aggregate.

In 2015 I described a blueprint for Bangalore 2030 but, while I still subscribe to this ideal, it has become clear that growing into it will require the same work to happen at all scales, inside neighbourhoods and across megacities. Bangalore is a legacy megacity. It will eliminate air, water, and noise pollution — eventually. But a hacker village need not endure industrial era growing pains. In the language of software projects, Bangalore is a multi-year refactor and the village is a from-scratch rewrite.

Like many of my friends, I find Bangalore too toxic in 2019 and I’m searching for alternatives. Successful hacker villages will have their own challenges when they, too, grow to populations in the millions: digital privacy, artificial intelligence laws, and bioengineering ethics are hardly solved problems. Thankfully, hackers love solving problems.

From blueprint to poured concrete

When we leave Pondicherry, conversation has already shifted from the potential to the real. We start planning a trip to the Kalrayan Hills to look at the proposed site of Ragul’s Hacker Village. It’s cool there, he says. Salem, the nearest city, has hot summers but the hills and their valleys stay comfortable.

Every location has its challenges. Our property in Nova Scotia is oceanside and metal or fabric, left to the elements for even a few days, will begin to rust or rot. Canada is cold and demands indoor heat just to survive. Materials are expensive, as are tools, and hired construction is out of the question most of the time. Perhaps cheap land is the only advantage Canada has to offer. That, and Universal Healthcare.

India, on the other hand, has very expensive land but cheap materials and labour. The weather in some locations is comfortable enough to eliminate the need for heating or cooling. Instead, extreme weather comes in the form of monsoons and even a modest village will require considerable storm sewers to manage the yearly assault. Multi-year rainwater harvesting is a necessity, since global warming has completely disrupted the heartbeat of India’s climate and rainfall is no longer consistent from year to year.

There will never be a one-size-fits-all blueprint for Hacker Villages, which makes the Hacker Ethos all the more important: free and open literature, documentation, resources, and education are a hard requirement for an activity which, by its very nature, demands mashups and remixes.

I’m excited to write about these Hacker Villages as they materialize in the hills and valleys. Whether we call them வழிகாட்டி கிராமம், Maitri Villages, or जादूगरों का गाँव, I hope an increasing number of people soon call them home.

Be gentle with the foothills when you begin your Hacker Village — this is a fragile ecosystem.

Be gentle with the foothills when you begin your Hacker Village — this is a fragile ecosystem.

Essay originally published on medium.com/@deobald (2019).