Two weeks ago, a friend struck up a conversation with me about his meditation practice. His query was:

Hi Steve,

I started meditating like a month ago. Nothing fancy, just sitting down and observing my breath. I did it because my anxiety was really, really bad and I couldn’t sleep at all most nights. It was horrible. At first the meditation made no difference. But then things started improving. Now after a month, I can get reasonable sleep on most days, and really good sleep once in a while And even on days I don’t sleep, my anxiety is not as bad as it used to be. This is great and I want to do it forever. Should I be reading something? I don’t want to get apps or make things more complicated than they need to be.

…to which I replied with my standard logorrheic brain dump. Eventually, I got my ideas across but he suggested that I sit down and focus those thoughts so that the next person could simply read a coherent essay.

Apps

There are few things in this world which make less sense shrink-wrapped into an app than a meditation practice, especially when your practice is in its early phases. I’d strongly recommend avoiding apps with two notable exceptions.

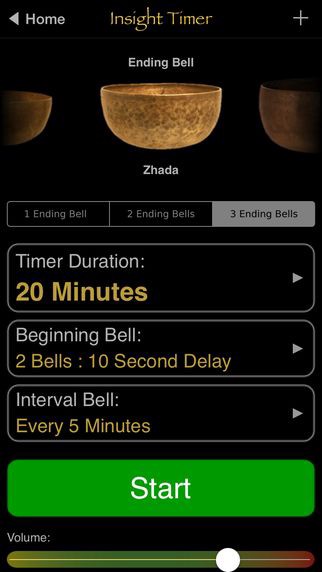

First, if you are the sort of person who benefits from the gamification of activities or a supportive community, you might find an app helps you stay on track with your practice. My friend’s practice has been self-sustaining, but for many people that simply isn’t the case. I can’t name an acute issue (like insomnia or anxiety) my practice resolves. It makes my whole life better, like exercise, sleep, and vegetables. But for that same reason, in the early days, I was often quite willing to neglect it. Initially I would meditate to a one-hour timer in my phone’s Clock app but I found that both the cute gongs and the supportive community in the Insight Timer app helped me maintain a daily practice, even if only a little.

The Insight Timer UI, once upon a time.

The Insight Timer UI, once upon a time.

The second case is that of specific practices with specific apps which support that particular practice. In the case of Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) there are …three?… official apps. Why three is beyond me. Why they cost money is also beyond me. But if MBSR is your thing, I guess you can dish out $10 a pop for these things. In my case, there is a dhamma.org app which offers basic Anapana (breath) meditation instruction for users who haven’t taken a 10-day course and about a dozen one-hour recorded meditation periods for people who have taken a course. I do use the dhamma.org app for one fairly boring feature: it tracks my meditation periods so I can honestly answer the question “how often do I meditate?” for myself.

The reason I hesitate to recommend apps to anyone is because of the risks posed by learning from an app. Apps are, more often than not, designed to sell you something… and your meditation practice isn’t something you should entrust to the base instincts of capitalism. Treat meditation like you would a new drug prescription. As with drugs, you can really harm yourself — don’t self-medicate. Find a flesh-and-blood teacher you trust. Then if the system of meditation he or she has taught you is augmented by an app, by all means, make use of that app.

Books

Unlike apps, which I think can create real problems for the new meditator very early on, books tend to have the opposite effect. Every book you read, meditation-related or not, adds tools to your meditation repertoire. Although there are a few meditation books I’ve read from authors who indulge in mystifying the reader, pointless handwaving, or self-indulgence, they’re usually easy to spot in the first half a dozen pages. I’ll reproduce the shortlist I gave my friend and then explain it, but first I first feel I need to strike off two items I often see people mistakenly reading in hopes of understanding meditation, Buddhism, or Buddhist practices.

When I first started meditating I naturally started getting interested in Buddhism. Turns out, most fiction written about Buddhism is pretty crappy. The aforementioned mistakes are Buddha, the manga series by Osamu Tezuka, and Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. These writings both tell the life story of Siddhartha Gautama and, in that respect, they are perfectly enjoyable. Buddhist mythology need not be confined to stories scrawled in Pāli or Tibetan. The danger both works present is in their painfully inaccurate interpretation of Gautam Buddha’s teachings. Buddha relies on repeated imagery of “the interconnectedness of all things” and Siddhartha falls even further with a meaningless interpretation of non-dualism which equates a man and a rock. These books will teach you nothing about meditation or the Buddha’s teachings.

The shortlist is obviously flawed and incomplete, but I may try to revise it as I come across work I wish I’d had when I started meditating.

Practice:

- Way to Ultimate Calm (Webu Sayadaw)

- Mindfulness in Plain English (Henepola Gunaratana)

- Tao Te Ching (Gia-fu Feng or Victor H. Mair translations)

- Nothing Special (Beck)

- Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (Suzuki)

- Not Always So (Suzuki)

Practical Theory:

- The Doors of Perception / Heaven and Hell (Huxley)

- Altered Traits (Goleman and Davidson)

- The Art of Living (Hart)

Philosophy:

- Meditations (Marcus Aurelius)

- Letters from a Stoic (Seneca)

- In The Buddha’s Words (Bikkhu Bodhi)

- The Timeless Way of Building (Alexander)

- Finite and Infinite Games (Carse)

This list requires some explanation. It exists on a spectrum and is ordered within the sub-lists on that same spectrum. At the top are some of the most practical meditation-specific books a meditator might look to for inspiration. At the bottom are books which do not deal with meditation directly but lend themselves to readings which will certainly boost a meditator’s analysis of what she is learning in meditation and perhaps provide guidance in the space between the mundane and the supramundane.

The Way to Ultimate Calm is a collection of talks given by Webu Sayadaw in his humble monastery to lay pupils. His teaching is direct and unambiguous yet warm and full of his sense of humour, even when translated from Burmese.

Mindfulness in Plain English has its issues. My caveat is to disregard his advice regarding bodily sensations. Most of the book deals with breath meditation and it provides plenty of background for that. If and when you want to start working with bodily sensations, attend a Vipassana course or a Zen sesshin so you can do so under the guidance of a trained teacher.

Few modern interpretations of the Tao Te Ching label it a manual for meditation, but I find it hard to read any other way. It’s paradoxes present the reader with meaningful koans which work on many levels and hidden in its eighty-one pages are the true “secrets” of meditation:

Controlling the breath causes strain.

Can you be as a newborn babe?

Are you able to do nothing?

…

Misfortune comes from having a body.

Without a body, how could there be misfortune?

Obviously, reducing one’s breathing to that of a newborn child and then using it to erase the body is… easier said than done. But there are many pages of the Tao Te Ching I have revisited over the years and found to express profound ideas in timeless language. My caveat with the Tao Te Ching is to ensure you do not pick up a Stephen Mitchell translation. Despite being the most common (as it seems he’s translated it dozens of times) it is easily the worst.

Nothing Special may not pertain to the beginner’s practice yet, but it does a fantastic job of answering some of the weirder questions which come up repeatedly during meditation practice. Beck is a straight-shooter and refuses to introduce mundane, surface-level paradox into her Zen teaching.

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind and Not Always So are not so straightforward and can, at times, border on the sort of mysticism that Zen tends to engender in its teachers. They are comprised of essays and talks, however, and you can probably pick up any one of them, read through it in a matter of minutes, and decide whether or not Suzuki is right for you.

The books in the “Practical Theory” category are more diverse and I wouldn’t say the three of them share much in common beyond their category. Huxley’s work is essential reading, in my opinion, for capturing Homo Sapiens’ global environment. Why does every culture drink? Why does the world seem to narrow and solidify with each passing year of human life? Why do humans seek something greater, in religion or spirit or booze or psychedelics or sleep deprivation or fasting or self-mutilation or meditation? Huxley has invested an inordinate number of days of his life attempting to answer these questions and his theories are worthy of consideration.

Altered Traits is far away from Huxley’s work but just as useful. The scientifically-minded will find solace in another lifetime of effort poured into the difficult science behind meditation. The author’s prefer the results of quantitative research performed with active controls and their standards are strict enough to disqualify all but 57 of the world’s roughly 8000 major meditation studies until now. There is hard science behind meditation and this book is the nexus.

The Art of Living is in a third category altogether. The theoretical aspects of Vipassana meditation, given as evening lectures during a 10-day course, have been condensed into this book. Available for free as both a PDF and audiobook, it’s perhaps worth reading before attending your first Vipassana course… but I wouldn’t count on it. I read this book before attending my first Vipassana course and it did little but confuse me. A Vipassana course is almost ridiculously systematic and the flow of these lectures follows that systematic teaching. Without the practice, they don’t mean much. [As a side note, the phrase “The Art of Living” was, uh, borrowed by Ravi Shankar (a student of S.N. Goenka’s) after he decided to water down, Hindu-ify, and commercialize the meditation he’d learned. Ravi Shankar’s organization has nothing to do with this book or Vipassana.]

On to philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations is not really about “meditating” in this sense, but it’s wholly applicable. Meditation itself is pretty… boring and straightforward. Follow breath, accept whatever is distracting you as being okay, come back to breath, repeat. It’s the outcomes that are interesting and I think Aurelius captures quite a few of those very well. Letters From a Stoic, similarly.

In The Buddha’s Words is more of a day-to-day manual. For those of us who were largely ignorant of Buddhist… anything… before we started meditating, In The Buddha’s Words captures some very simple aspects of everyday life which do, oddly enough, come up in meditation. The Buddha wanted you to meditate, sure. But he also wanted you to do the dishes, brush your teeth, and give gifts to your friends and family. For those of us caught up in meditation it can become easy to forget about some of the basics that meditation is supposed to bring us back to and this book is a handy reminder.

The Timeless Way of Building is ostensibly a book about architecture but it reads like a bible. In the leaves of this wonderful little work of art are hidden instructions for optimizing the surface area of strawberry slices to maximize flavour. And other stuff. Like Doors of Perception, this book stands at the nexus of our environment and our innermost psychology and I couldn’t recommend it more highly.

Finite and Infinite Games was my most debated addition to the list but as many meditation experiences are entirely ineffable, one needs to look to literature which approaches the problem from a completely different angle. If you start reading this and it doesn’t strike you, Winnie The Pooh and The Little Prince make acceptable stand-ins.

Teachers

I gave my friend some specific recommendations regarding meditation centres and one zendo near Bangalore, but I realize that those suggestions won’t apply to most people reading this. My general find-a-teacher advice is to start with a Vipassana course and work your way backward from that. You won’t find an experience deeper or more intense than Vipassana, but that’s not to say it’s the best or only practice you should bother with… just that it will take you to the depths of meditation so you can decide how deep you want to go, long term. I have a number of friends who have sensibly chosen the Zen path and if you don’t feel ready (or able) to attend a Vipassana course, a Zen sesshin is a valuable experience and a good opportunity to decide whether the local teacher is someone you want to entrust your practice to.

There are also many worthwhile teachers teaching Samatha (Anapana) and Vipassana meditation at a different pace but it becomes increasingly difficult to help someone find an appropriate teacher as the teachings become less and less systematic.

I hope this little blurb has been of use to you! I would love to hear feedback on the book list and other recommendations. Take care.

Essay originally published on medium.com/@deobald (2019).