How often do we experience real silence?

How often do we experience real silence?

Universal Spaces was written out of necessity. There is nothing profound about the idea of universal spaces — spaces without any form of exceptional availability — but no preexisting terminology satisfies the requirement of defining spaces only in terms of that quality. Universal spaces require an identity, something we can point to when we presuppose them as a superset of Silent Spaces.

It is quickly becoming cliché to attack contemporary human habitats as a hellish landscape: cities screaming incessantly in the tone of exploding fossil fuels and painted in the colours of technological overstimulation. But it is no less true for these repeated acknowledgements. Rather, this points to our acceptance of our noisy, intrusive world. The volume differs from neighbourhood to neighbourhood and country to country but at one volume or another we have come to expect noise pollution as a default characteristic of our environment.

A Silent Space is a universal space with the single purpose of turning the volume down to zero. It exists so its visitors may experience silence. To meditate. This is a recursive definition where meditation means any silent and introspective activity. Whether one adopts the Stoic definition of meditation, of deep and penetrating thought, or the religious definition of solitary prayer, or the attention-based definition of intentional practice, a Silent Space exists for the purpose of meditation. Silence is a prerequisite of meditation.

The home as a Silent Space

By dictionary definitions alone, universal spaces and silent spaces are self-evident. Due to this obvious nature, a Silent Space may not seem special at first. For example, people are often tempted to point to a library as a silent space. A library or a park is a quiet space, not a silent space. As there are many spaces which are nearly universal spaces, there are many (perhaps many more) spaces which are nearly Silent Spaces.

A Pattern Language describes a number of such locations. Patterns such as Sacred Sites, Quiet Backs, Holy Ground, Common Land, Zen View, Tree Places, and Garden Seat all speak to something adjacent to Silent Spaces. However, each of these architectural patterns adds or subtracts something from unadulterated silence (or unadulterated universality). Christopher Alexander’s writing highlights comfort and habitability as the crux of good design and therefore frequently paints images of the home, so let’s start there.

First we must acknowledge that almost no one’s home is a universal space. The home, by its very nature, tends to be an incredibly exclusionary place. When we are not in our home it is usually empty. We return home to find solitude and, once there, we invite only those with whom we want to share the space. Some homes are more universal than others, of course. During the Mumbai Floods and the Chennai Floods many households opened their doors to complete strangers, offering them food and shelter. My mother once ran into some cross-country cyclists at the grocery store and invited them home to stay the night. A friend’s mother recently said, as we were leaving her house after a week of her hospitality, “you too are our children — you are welcome in our house any time.” I can think of many people capable of extraordinary generosity which far outstrips what I will ever achieve in my life. But most households do not open their door to the general public.

Universality is a spectrum with binary folds: Universality is on one side and Discrimination is on the other. Even though private homes are fully within the discriminatory half of this binary, there are increments within this half which inch them toward universality. It is in these less discriminatory homes that we see the tension between silence and universality; as one’s home becomes more welcoming and more universal it tends to become less silent. More people often mean more noise, more politics, more jokes, more music.

Charlotte Joko Beck writes in Nothing Special about a story she tells her students, a small pseudo-allegory involving her meditation practice. She sits in front of a locked door in the attic, meditating. After many hours of meditation, the door will finally open so she can go inside but she finds it only leads downstairs to her front room. She goes back up to the attic to find the door is locked again and she must start all over. However, every time the door unlocks and she passes through it there is more life in the front room. More guests, more family, more activity, and more shared experiences. The door represents the challenges she experiences in meditation but the guests are literal and the attic may very well be where she meditates — a silent space within her home. I do love this allegory but it leaves me to wonder how often these guests are welcomed into the attic.

My first Silent Space

Have you ever walked past a prayer room in an airport? They are usually tucked off in a remote corner of the terminal, hidden under escalators or down an unmarked hallway that seems covered in an invisible Staff Only caveat. Have you ever wondered what they’re like inside or what goes on in them?

The common prefix “multi-faith” always intrigued me but, having no faith to speak of, I could never bring myself to even sneak a peak through the door. That is, of course, until I learned how to meditate. Meditating at home can be difficult simply because it is home. Puttering, exercise, books, or a pot of tea all sound a great deal easier and more enjoyable than the hour of hard work meditation usually implies. But airports are bright, loud, uncomfortable places. I rarely want to read or write in an airport and every sip of tea just reminds me how much more likely a bathroom break during the flight will be thanks to my small caffeine indulgence. My first Silent Space was a multi-faith prayer and meditation room during an eight-hour layover and it wasn’t silent at all.

First of all, the space was divided in a way I found peculiar. Near the door there was an inviting plaque insisting I could use the room as long as I remained silent. The plaque had a large graphical ring of all the world’s religious logos enveloping a cartoon Earth. It included the standard entries plus more esoteric religions like Zoroastrianism, Taoism, and Bahá’í. There were some logos I didn’t recognize. All faiths were welcome — including no faith at all. Between the inclusion of the word “meditation” in the room’s title and the explicit mention of the faithless (like me) I was convinced the space would be functional for the purposes of secular meditation. But as I took off my shoes and walked in, I found the room divided into three clear sections: Islamic male, Islamic female, and Generic Christianity. I really didn’t belong in any of those categories but I could find a spot to sit cross-legged by process of elimination: I’m a man and the section for Christians was full of chairs so I defaulted to sitting on a rug on the male Muslim side. I was the only one in there anyway and I figured it didn’t matter a great deal.

I was half an hour into meditating when people started to trickle in. I heard some women whispering quiet prayers on the other side of the curtain. I heard a man come in and lie down for a nap, despite signs all over the room declaring NO SLEEPING in bold type. Someone’s mobile phone rang and he quickly silenced it. My foot hurt. This meditation was more difficult than I’d anticipated but it was completely disrupted when the prayer battle started.

My meditation was already in a shamble of paranoid thought (am I offending anyone? should I not be sitting on this rug? will someone ask me to leave?) when the volume went up on the Christian side. A prayer suddenly became substantially louder from over there and a fire-and-brimstone epic, probably from the Old Testament but possibly from Revelations, began to take shape. My eyes were closed so I wasn’t sure how many people I was sharing my third of the room with but it included at least one Muslim man who wasn’t having any of this crap. His prayers became both louder and more musical in an attempt to dwarf the fellow reading his favourite biblical passage on the far side of the room. The haunting musical chants beside me were set upon by Christianity’s weaponry of prayer: repeated crescendo. Phrases like And God said unto him! were at a near-shout now, flanked by a false nadir of prayer that was equally haunting and shouted just-quietly-enough-so-you-know-this-is-the-quiet-part.

This continued. By this point I had a smile on my face and I’d completely forgotten about my foot as I couldn’t believe that this was what went on in these multi-faith prayer rooms, a hilarious rap battle of belief structures bundled up in scripture. They should sell tickets! This is a thousand times more interesting than anything else that’s going on in the airport, I thought. I was convinced my meditation experiment had failed but the prayers eventually died down and most people left. The timer on my phone gave a little gong and I opened my eyes to see a middle-aged man praying silently with his head on the floor and his son staring at me, mind cranking away behind the round whites of his eyes, visibly bewildered at my presence. I don’t know what I’m doing in this room either, kid.

I put my shoes on and went to go find a cup of tea.

The secrecy of Silent Spaces

It is by design that an airport’s “prayer room” or “meditation room” is hard to find. In the same way that universal spaces often give way to Lesser Universal Spaces, Lesser Silent Spaces — quite common and relatively easy to find — are usually protected by a religion. Because airport prayer rooms would likely come under a lot of flak from the New Atheists and adjacent belief systems if they weren’t deemed universal, there is usually a plaque declaring them as such. The New Atheists, with their arbitrary and academic interest in the universality of public spaces, get their way and atheists of all statures rarely set foot in the prayer room… everyone wins. But the airport shoves the chapels, prayer rooms, and meditation rooms in remote corners with minimal signage just to make sure heathens aren’t tempted to spend their layover sullying a silent space.

In my experience it’s a rare occurrence to find the meditation room from airport maps, google maps, or signage. Years after that first prayer room experience, I have tried to find the meditation room in every airport, even if I don’t have time to use it. This exercise usually requires speaking to the Information Desk and in some cases even they won’t know where it is.

The airport example again speaks to the tension between the silence of a space and its universal nature. Democratization is expensive and the currency is comfort. An airport meditation room is technically universal but hidden in such a way as to discriminate against anyone who isn’t determined to find it. This is necessary. As systems exist to prevent patrons from changing a bicycle tire in a public library, systems exist to prevent patrons from making noise in a Silent Space.

But society’s classic spaces for silence take this discrimination to the extreme. While most religious buildings welcome all visitors, the institutions which own those properties and support these visits usually prefer visitors who already wear their logo. There are exceptions. Sri Lankan Buddhist temples are not intimidating in the same way temples from other Buddhist sects are. Very old churches and temples may transition, at least in part, from religious space to historical landmark — yet retain a silence rule, written or not. The Bahá’í Lotus Temple in Delhi welcomes all visitors for silent meditation and contemplation. But in general, the silent spaces of religions have a certain level of secrecy to them even when they are built in plain sight.

Many other Lesser Silent Spaces choose to do away with universality entirely. Democratizing a space, to any degree, comes at an expense. But thrift in the currency of comfort saddles visitors with other costs in the realms of economy and status. If you are willing to dispense with universal access, your silence is easier to maintain. Build a spa, resort, or themed hotel. Alternatively, build a hidden commune with hippie ideals, a mysterious and uninviting donation-based permaculture farm, or an invite-only sanctuary.

The tension between silence and universal access is real and the choice to make a silent space exclusive is understandable. Lesser Silent Spaces need not be condemned. However, as our collective and individual worlds close in on us, from the street and from our phones, we need to look for Silent Spaces which choose to exist as selflessly and as virtuously as the humble public library.

As with libraries, access must exist in every town and neighbourhood. If libraries are the antidote for illiteracy, silent spaces are the antidote for noise. The weight of illiteracy is linear. Noise, on the other hand, burdens society with its multiplicative nature. Noise first accumulates, then escalates, stacking sound on sound is an arms race, competing to be heard. If a horn can’t be heard over the diesel engine of a truck, we get a louder horn. If our friends can’t hear us over the jackhammering and traffic, we shout into our phones. The city. Nowhere is the antidote of silence so desperately needed.

Noise poison and the city

Try googling for “silent spaces”. The results are enlightening… and a little sad. There are a number of noble endeavours listed such as parks and community projects which endeavour to provide citizens with a space for silence in urban spaces. Dig through these websites, however, and the limitations of these projects emerge. First in expectations of the spaces themselves:

How different might life be if green places for silent reflection were easily accessible to us all? … For a couple of hours each week, visitors to these quiet areas were invited to switch off from technology and to stop talking.

And then of the visitors’ requirements:

Even as little as five minutes will help us to enjoy the restorative benefits of being peaceful in a green place.

The assumptions that a Silent Space will be effective on a highly restricted schedule or that it must exist outdoors both have obvious failings. Making time for silence is hard enough for most people; forcing visitors’ schedules to align themselves with the “silent time” schedules of their local park is untenable. Outdoor spaces, particularly green spaces, have myriad admirable qualities (many of which are described in impeccable detail by Alexander in A Pattern Language) but… sometimes it rains. Even a twenty-four-hour Silent Space is of restricted use if it has no indoor component. Lastly, the idea that silence only needs to be available in the same five-minute doses in which we receive YouTube videos is obviously insufficient for those who require it in minimums of one hour. While these silent spaces are imperfect they are still Universal Silent Spaces — and any city with such spaces benefits from them.

Returning to our google search, we don’t need to scroll far to find truly dystopian interpretations of “silence”: This eponymous noise-masking device for shared office spaces listens to the noise level in the office and generates more white noise to mask the din. This is not progress. This is escalation.

I have come to think of the usual term noise pollution in other terms: noise poison and noise weapons. Labelling urban noise as pollution brings up the wrong connotations: self-victimization, othering, and blame. Pollutants are abstract and they don’t immediately identify themselves with those who suffer their consequences. Poisons hurt us and we need to spend as little time with them as possible. Weapons hurt others and we need to wield them as conservatively as possible. When it comes to noise, we need to stop hurting ourselves and we need to stop hurting those around us.

I am in a street-side cafe. I can hear a bird, a phone ringing, a business conversation in Hindi, a phone call in Kannada, an angle grinder in a construction site across the road, the azaan from a nearby masjid, the putter of a small lorry, the prolonged and violent honk of an impatient but otherwise impotent taxi, and —miraculously— the flutter of leaves in the tree beside me. The sound of the city tells me that it is alive. Commerce is happening, people are engaged in their daily activities and the neighbourhood throbs and hums with the work of automata within this superorganism. Even a city as scattered and chaotic as Bangalore is beautiful and tempting. There are very good reasons thirteen million people live here.

The tree beside me, a construction site in the background

The tree beside me, a construction site in the background

But the city is poisoning us. Day and night, shouting, honking, bells, political rallies, religious festivals, two-stroke and diesel engines pound on the windows. We get to work and put in earphones to drown out loud phone calls and conversations (or, god forbid, turn on the office noise-masking device). We get home and poison ourselves with Netflix. The sound is incessant. Since the dose makes the poison, we simply need to dilute it. As we become less poisoned, we will be less tempted to inflict this poison on others. If we want to dilute the poison for everyone, even selfishly, so that society’s reciprocation mirrors our own and all the weapons of noise are dulled, then the space without the poison must be available to everyone.

The antidote must be universal.

Meditation Centres

It is almost impossible to identify true Silent Spaces in our cities, save a few sectarian, albeit universally welcoming, examples. Most spaces which happen to be silent are simply not universal.

Meditation centres are a collective exception; spaces designed for meditation are spaces designed for silence. Quite a few fall into the trap of sectarianism, and thus exclusivity, or part-time silence, filling other times with festivals and noise, but spaces designed for the singular activity of silent meditation tend also toward universality. Silent Zendos and Vipassana Centres are good examples but Vipassana Centres are more consistent.

Vipassana centres around the globe are designed in the same way, run entirely on donations and volunteer efforts. Courses are free and anyone is welcome to apply to take an introductory 10-Day course to learn how to meditate. All Silent Spaces come with restrictions and this is the key restriction of a Vipassana Centre: you must know how to meditate as an old student in Vipassana to make free use of the centre. In fact, the restrictions of Vipassana Centres are actually a bit stricter than this. They remain universal spaces, however, because they are strict in terms of their uses, not their users. Silence is escalated to Noble Silence. Not only is the meditation hall of a Vipassana Centre free of talking and phones, Noble Silence forbids touching, eye contact, reading, writing, and bodily noises.

Because of this strict focus on a precise definition of silent and an individual form of meditation, the universality of formal meditation centres is far from perfect. If I need a couple of hours to think deeply about a difficult problem in silence, a Zendo or a Vipassana Centre is not the space for it. Thankfully, not every Silent Space must incorporate these strict rules. Meditation centres provide us with an architectural aspiration. Their extreme example is a template of what humanity will soon need to build into every neighbourhood of every town or city.

A Canonical Silent Space

The canonical Silent Space

The canonical Silent Space

The canonical Silent Space is almost painfully obvious but it does have some distinct and non-negotiable characteristics. There must be:

- Signage

- Sound barriers

- A building

(Optional features might include such basics as public toilets and drinking water taps, provided there is someone to maintain them. But they are not essential.)

Signage should be posted in clear view, in all relevant languages, explaining unambiguously that visitors are in a Silent Space. In Bangalore, such translations of the local Kannada would definitely include Hindi, Tamil, and English. It would be advisable to include Telugu, Marathi, and Malayalam. Clarity and disambiguation is the aim of such translations. The level of detail depends on the space. The large, one-word SILENCE sign at the beginning of this article was enough to keep anyone from speaking, running, clapping, or using their phones when we visited the Theosophical Society Gardens, where I took that photo. If the space is meant to elevate silence from simply external to internal, disallowing physical bodily contact, sleeping, or reading, it should mention this explicitly.

There will be little debate about the fact that flora make the best sound barriers. Most architects of Silent Spaces surround them with trees, perhaps constructing walls around the trees, often making the route into the Silent Space indirect to prevent sound from entering. When the land available to the Silent Space is limited, recessing the entire space into the ground and adding shrubbery to trees helps dampen the sound from nearby roads and buildings. The internals of the Silent Space might include additional greenery or outdoor seating.

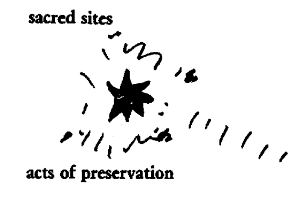

When designing a Silent Space, it would be wise to exploit any of the adjacent patterns from A Pattern Language. Shelter for the space suggests at least two obvious patterns: Sacred Sites and Holy Ground.

Whether the sacred sites are large or small, whether they are at the center of the towns, in neighborhoods, or in the deepest countryside, establish ordinances which will protect them absolutely — so that our roots in the visible surroundings cannot be violated.

… And above all, shield the approach to the site, so that it can only be approached on foot, and through a series of gateways and thresholds which reveal it gradually — Holy Ground (66) …

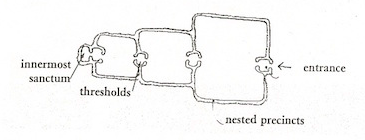

Holy Ground helpfully complements, and expands on, this idea. In the Holy Ground pattern, multiple sound barriers are elevated to thresholds which provide an intuitive understanding that the space is silent and demands a visitor’s respect:

In each community and neighborhood, identify some sacred site as consecrated ground, and form a series of nested precincts, each marked by a gateway, each one progressively more private, and more sacred than the last, the innermost a final sanctum that can only be reached by passing through all of the outer ones.

Alexander’s patterns leave it up to the imagination of the final architect to determine what belongs in at the centre of a Sacred Site, the innermost sanctum of a Holy Ground. We do not. At the centre of a Silent Space is the location of maximum silence: a building for meditation. As simple as a small pavilion or as impressive as a full-blown temple or meditation hall, the specifics of the building do not matter. If it protects meditators from the elements and adds to the diffusion of sound, it serves its purpose.

A universal meditation hall in a universal silent space is best left unadorned — no logos, no sculptures, no paintings. If these decorations are added, try to keep them to a minimum or you soon risk ostracizing potential visitors. Think of meditation rooms in airports — include features which feel inclusive and avoid those which give preference to a particular philosophy, belief, dogma, or sect. Chairs, floor mats, and cushions are necessary seating. A statue of Buddha or Ganesha serves no practical purpose.

Gandhian economics are dead and at no point will society in the large turn back to a simple agrarian lifestyle in the hills, no matter how attractive or romantic this may seem. A few of us may run away to join the one-straw revolution, but our cities will experience accretion for a long time to come as the majority of humanity abandons a rural existence to populate them.

Earth’s cities should be a joy to live in. We should be free to enjoy both the high energy and activity that these hubs of society represent and frequent pockets of silence and reflection within them. Universal Silent Spaces can be counted on one hand in most major world cities today, but as both silence and meditation are claiming mindshare across the world we will need a Silent Space in every neighbourhood.

Neighbourhood ubiquity requires an appreciation for Silent Spaces which will only emerge once the spaces themselves begin to emerge. This emergence will be twofold between the creation of new Silent Spaces and increasing awareness of existing Silent Spaces. Initially, it will be frequent travellers who are most likely to require Silent Spaces as they develop a daily meditation practice and quickly find that a truly silent room, open to anyone, is a very rare occurrence everywhere on the planet.

The next article in this series will be a call for proposals. The Silent Spaces Project (or perhaps The Suññagara Project?) will map and describe all the Silent Spaces across the globe so meditators and seekers of silence will never feel trapped when traveling away from home. Let’s start with the airports?

arraññagato va

rukkhamålagato va

suññagaragato va

Essay originally published on medium.com/@deobald (2019).