In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari repeatedly emphasizes the need for society to apply critical thinking to the future of software, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. Harari is one of the more forward-thinking philosophers when it comes to disruptive technology and 21 Lessons lucidly collects the requirements for our species’ future: our new tools must sustainably respect future arcs of aggregate data use and they must do so globally.

This is no simple task. To respect the future of data is to anticipate it and we will often be wrong. Aggregate data use is the province of statisticians and data scientists today — of artificial intelligence tomorrow. Knowing when and how we need to respond to the risks posed by our own creations is a daunting task. It requires that we play to our strengths and trust in the science of disciplines beyond our field of expertise.

In Steve Yegge, You Are Half Right (Part One: An Ethical Void) I proposed a thorough reexamination of today’s startup economy and its reckless offspring, using Yegge’s article about the Southeast Asia ride share economy as a bit of a punching bag. I mean him no disrespect but his views are a loud echo of the majority and I’m a dissenter. Since I am first and foremost a technologist, in this article I will shift focus — from the present to the near future and from business models to technology.

The problem

Amir Omidi, regarding Slack’s unwarranted account ban.

Amir Omidi, regarding Slack’s unwarranted account ban.

This December, Slack users got their umpteenth sampling of the dangers associated with centralized services. Although Slack has a notoriously fragile Privacy Policy and weak service record, the fundamental problem is not Slack’s policy-making but its business model. I choose to pick on Slack because it is the antithesis of sustainable technology in a crowded market. But this fragile business model is the status quo. Slack is fragile for the same reasons Grab and Airbnb and Dropbox are fragile: unencrypted data delivered exclusively over a central point of failure to an end product the buyer does not own or control.

If you are a programmer, the first networked application you wrote was almost certainly a chat service of some sort. It might have been distributed or a simple client/server design. It might have been CORBA (like mine) or it might have been written on top of HTTP. It might have transferred binary blobs or JSON. It doesn’t matter. For programmers, chat feels like a solved problem.

![]()

It’s not.

Even if you’ve never written a line of code in your life, you’ve almost certainly used chat. A chat. Some chat. But not the chat. Normal humans will remember Google Talk, ICQ, and MSN Messenger. Nerds maintain their nostalgia with memories of IRC and their optimism in Matrix. My friends and I all have Slack and Signal and Keybase and we are disappointed in each service. Slack is unencrypted and provides its service on a whim (apparently). Signal is ugly, slow, broken, and undistributed. Keybase has a closed source server and a design that could hardly be more confused.

There is no single protocol to which we can ascribe the notion of digital chat the way we can with digital mail — but there should be. Why doesn’t it exist?

Encryption

Data needs to be encrypted. It wasn’t long ago that intentional encryption use was limited to security-conscious nerds, techno-preppers, and governments. In a few swift years, trolling, doxxing, and identity theft have jumped from the esoteric language of mailing lists to household names thrown about by national news anchors.

Public awareness of cryptography has been assisted by two watershed releases: Bitcoin, in 2009, and WhatsApp end-to-end (e2e) encryption, in 2016. [1] All features of quality software live on a spectrum and of them cryptography is the hardest to quantify. End-to-end encryption implementations are numerous and there is debate about which approaches to e2e should be considered safe at all. (In the broader world of cryptography, the math used in Bitcoin bears no resemblance to that of WhatsApp’s e2e message encryption; it’s an apples-and-oranges comparison and not meaningful to this discussion.) What matters to the global user base is not the specific algorithm or the lengths to which one must air gap that algorithm to make it truly secure. When six-and-a-half billion literate humans care about cryptography they care about higher levels of abstraction. “Can my government see my casserole recipe? Can the police see these naked photos of me? Can the 4chan trolls rally a small army of the socially inept to make rape and death threats against my family?”

One fourth of that global literate population uses WhatsApp today and with every message they send they are taking encryption for granted, whether they know it or not. For them, it is granted. WhatsApp has no option to turn e2e encryption off. Users can dump their unencrypted messages on Google Drive but they will always be encrypted in flight for a definition of “always” that equates to “as long as Facebook, Inc. sees fit.”

As an entrepreneur or software architect, you have little choice about whether or not you encrypt the messages your software creates or consumes. If those messages are essential to the success of your business, sooner or later you will encrypt them. When you do, you will care about the algorithms you choose. Your users, on the other hand, will care when and if your choice fails to keep them safe. Your B2C users don’t want to be spied on and your B2B users don’t want their business laid bare for other entities to train their AI models on. In less than a decade, the act of encrypting data means as much to the average business as paper shredding did in the previous decade. In another decade, expect every business to put “encryption” in the same essential asset category as “email server.” In the grand scheme of things it probably doesn’t matter much which email server you choose — but you definitely have one.

How will businesses guarantee that this essential feature of encryption is trustworthy and sustainable in the services they pay for? No business owner trusts their entire company to Facebook, Inc. or Slack, Inc. Those who do so will quickly reconsider the moment a staff member checks her Slack messages while attending a wedding in Iran. Whoops! The whole company is banned from Slack because she has friends in other countries. Again, keep in mind that the problem isn’t Slack but Slack’s business model. Keybase, for all its fancy encryption, is no better.

Sensible businesses cannot put their faith in a single corporation or even a single government; change at that scale happens too quickly in the 21st century. Since encryption over a single point of failure is meaningless the businesses of the coming decade will inevitably stop relying on services with a single point of failure.

Federation

Services need to be federated. Slack can close down your company’s account without notice, Uber can fire you without reason or recourse, and Dropbox can share “anonymized” data about your files you thought you had safely stored in “the cloud”.

Some folks in the tech industry tend to throw around “distributed” as a synonym but that word already carries some heavy connotations and dilutes the understanding of the user as to which risk it mitigates. Slack, Uber, AWS, and Google are distributed for some definition of “distributed.” They operate in multiple data centres in multiple countries. Their network architectures, data stores, and runtimes are all redundant. But they all share a common point of failure: the corporation. [2]

In Sapiens, Harari solidified in our minds the understanding that homo sapiens’ shared belief in — and cooperation around — imaginary entities is what brought us our present success as a species. Some of these entities are more plastic than others. Money is more plastic than gods or states. In a world where we hand more and more control over to corporations in exchange for the useful services they provide, we need a method of introducing plasticity to corporations. This plasticity is called federation.

Federation is a little difficult to define because it is a nebulous concept which describes, well, a nebula. Federation in software is not all that different from its physical world counterparts. Cooperative federations, for example, pool individual cooperative corporations into a unionized corporate body to achieve higher goals. Federated software services pool individual services into higher goals. Imagine that in 2028 the world governments get tired of a broken, centralized Facebook ruining all their elections; they dismantle Facebook and federate it. The federated Facebook of 2028 allows you to use any Facebook-compatible client to connect to any company running a Facebook-compatible service. Compatibility is defined by an Internet Engineering Task Force standardized RFC describing the Facebook Protocol and users choose a service provider which meet their needs: pay a monthly fee for an ad-free experience or use a free service which serves up ads and recommendations. Not happy with Service X? Move your data to Service Y. All your images, messages, and contacts are compatible across networks in the same way email messages from @deobald.ca can find their way to Gmail’s servers containing @gmail.com email addresses. The many Facebook services of the future each make a lot less money than the Facebook, Inc. of 2018 — but they also cause a lot less damage.

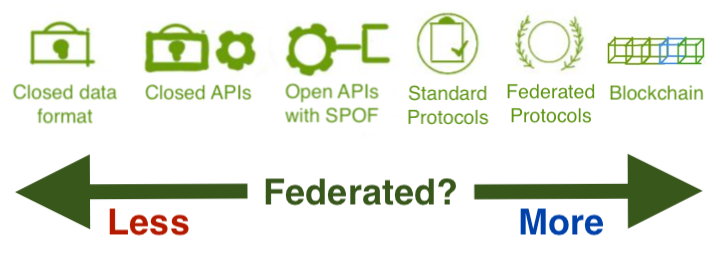

Federation, like encryption, lives on a spectrum. Thankfully, federation is easier for everyone to understand at various points along this spectrum. It also has many meaningful analogues in the physical world.

Everyone will have a different total ordering for the items on the federation spectrum but most people can probably agree on some basic partial orders. Open data formats are closer to federation than closed data formats. An API which accepts messages from a foreign server node is closer to federation than an open API which only accepts messages from clients. The blockchain is the most distributed and most federated networking technology — and we have negligible real uses for it. That sort of thing.

A sample total ordering might look like this:

Not everyone is familiar with all of these concepts but most of these are easy to understand with examples. In 1998, an .xls file from Office ‘98 was a closed data format. Google Maps provides an open, commercial API with a single point of failure. HTTP is a standardized protocol. SMTP and XMPP are federated protocols. But the most successful federated services are easiest to understand when we use their household product names: Telephones. The Web. Email.

It is unreasonable to expect we will ever live in a utopia of perfectly-engineered federated services. Designing a good protocol is difficult and it’s often profitable in the short term to take an easier way out. But there is always value in pulling services to the right end of that spectrum, even if it’s just from closed format to open format or closed API to open API. Regardless, the clear unifying theme seen in those examples — which pulls them toward federation — is openness.

Freedom

Services need to be Free. It is hard to trust encryption software that isn’t Free or open source. WhatsApp makes internal design trade-offs and asks that you trust Facebook, Inc. not to build backdoors. Even if the loopholes of closed source encryption and threat of backdoors never materialize as failings, closed hardware ensures the least trustworthy hardware sits right in the hands of the user.

It is equally hard to trust federated software that isn’t Free or open source. We trust SMTP servers like Microsoft Exchange and GMail to respect the protocol despite the fact that they are closed source; the SMTP protocol simply outweighs them. Newer protocols like Matrix and underused protocols like XMPP do not carry this weight and cooperation via federation demands that their first successful installations be Free. If the reference implementation of the Matrix server were closed source freeware or a Google service, users would have no reason to believe the protocol was destined for future success. What’s to stop Google from shutting down federation of closed source services? Correct: nothing.

Innumerable time sheets have been thrown into the fires of the Free/open software debate and I don’t intend to do that here. [3] If you don’t already believe Free software carries inherent value, I want to convince you of that fact about as badly as I want to convert a climate change denier or explain the health and economic benefits of the smallpox vaccine to an anti-vaxxer. For everyone else, I want to explain the mode of Free software I’m suggesting.

I am not discussing Alpha Nerd open source. The labyrinth of open source libraries and tools on GitHub are not at issue here, nor are well-meaning hacker tools like plaintextaccounting.org or org-mode. There are open source projects which succeed, to varying degrees, at marketing, design, profitability, and engineering. The designers of tomorrow’s protocols have their hands full as they will need to bake in all of these success factors from the ground up.

It is possible to design and build a successful, global, federated protocol in a suburban garage. It’s just a lot more likely to happen in the headquarters of a multinational corporation or the mailing list of a standards task force.

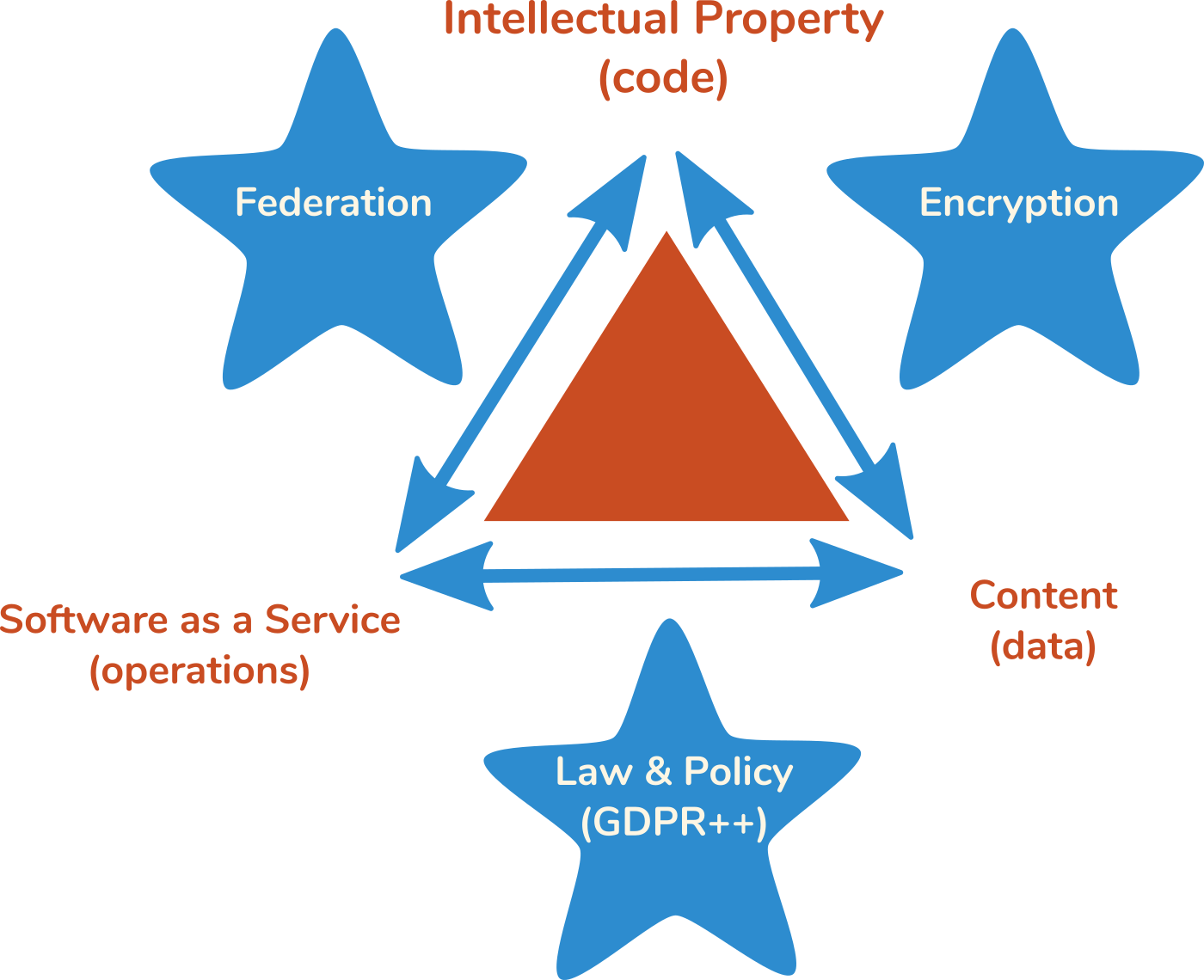

The software ethics triangle, version 1.0

I have worked on the structure of EFF (Encrypted, Federated, Free) Software for a long time and its initial incarnation looked something like this, in diagram form:

Notice that the original nodes of the triangle were outcomes, not prescriptions: code will be open, content will be owned by users, and only operations (services) will be charged for by software companies.

This diagram could be worse but it was more than a little naive and it did not announce a clear stakeholder: GDPR is decided by a multinational governing body but federation is largely a choice of a company providing a particular service. The triangle lacks symmetry.

The nodes (code, data, and operations) may at first appear to be technology-focused but they are, in fact, today’s business models. There are other names for these business models. Some would call it selling a product, a service, or data. Or SaaS, IP, and content. A company which exploits more nodes of the triangle has, in the short term, built a more fragile system in exchange for a more profitable business. Slack sells you use of their IP as SaaS and sells your data to third parties — that’s all three. Unless you’re an advertiser, Twitter and Facebook don’t sell users anything — remember that when software costs you $0.00 you are the inventory, not the customer. Their customers (advertisers) buy use of their IP as SaaS; that’s two nodes of the triangle. AWS arguably sells the least fragile system in this set of examples: SaaS, often built on open source IP.

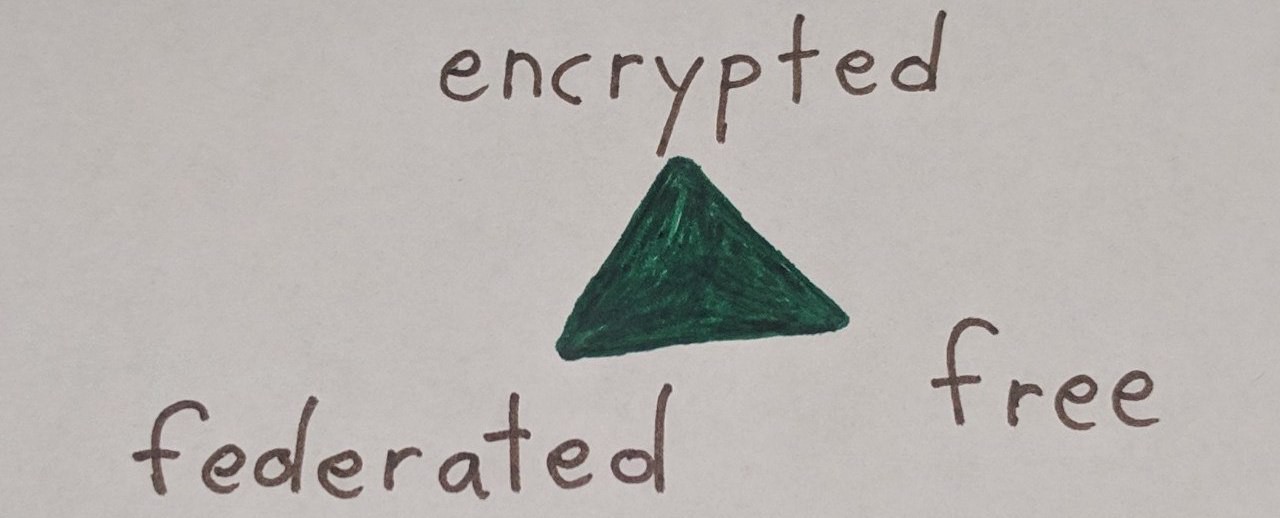

To avoid wishful thinking about world governments, version 2 of this diagram is focused on engineers and technologists like those who work at the aforementioned companies. The scientific community went through a pubescent stage in which it learned to appreciate and apply ethics. The broad field of technology is now screaming for ethical standards and they are much easier to apply to historical software like Twitter, Slack, and Uber than they are to disruptive AI and biotech. A strong ethical base in today’s software will help ensure we make fewer mistakes with tomorrow’s. Hence, the triangle looks more like this now, quickly doodled in marker:

EFF (Encrypted, Federated, Free) Systems are ethical. They do a better job in an environment of ethical regulation but they do not require it. These are merely the pillars of well-engineered ethical systems which, as a bonus, avoid fragility.

The sexy ethics of design and the boring ethics of policy-making

Every contemplative hacker I know thinks about policy, even if it is largely out of their hands. My old colleague Shafeeq once described its universal nature:

Governments regulate the wireless spectrum precisely because it is a national resource. The services built on top of regulated resources become inherently federated and it seems like the time is ripe to regulate one of the nation’s most precious resources: the privacy of its citizens.

Martin Tisné agrees, but suggests that data ownership will soon not be enough and governments need to go a step further to construct a bill of data rights. He seems to assume Free software as part of his ethical framework for his imagined future of data rights:

The team examines the algorithm used by the study and discovers the link to the employment profiling.

“Examine the algorithm” means “read the source code.” If we hope to have data ethics applied at this level, we had better we build a solid foundation for our lawmakers.

Policy ethics are boring ethics not because they don’t matter but because we have so little agency over them as technologists. The fight is worth fighting but unless you work at the Electronic Freedom Foundation or the Free Software Foundation, the fight probably isn’t your day job.

On the other hand, when we hear “design” many of us still conjure up images of architecture magazines and slick iPhone apps. Ethical design tends to be a lot less sexy and a lot more hard work. The hard work we put into federation prevents vendor lock-in; the hard work we put into localization and internationalization prevents culture and language lock-in. With any luck, policy will guide, and even enforce, good design but the ethics of EFF Systems must coincide with questions like “does this run on low-power devices?” and “will message delivery be guaranteed in areas of weak network connectivity?”

We can’t build everything all at once. You will be forced to choose between the EFF ethical pillars and design. Leave yourself room to grow.

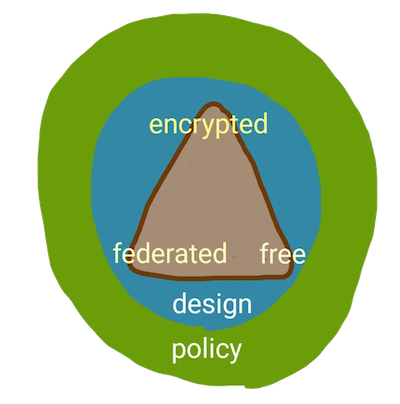

This ridiculous doodle [4] is our final Software Ethics Triangle. The nodes of the triangle are our pillars, all interdependent: Encrypted and federated services necessitate open source licensing. Federated software which sends unencrypted messages isn’t safe and encryption without federation guarantees that sooner or later, you will lose access to the service or lose your encryption. Open source software services which lack encryption or federation are as backward as any equivalent closed source software. The three pillars form a totality. Design is not a pillar; ethical design is what will make your service a success above and beyond its bare utility. Policy sits outside of, but adjacent to, design. Your software company probably has little agency over policy but policy may dictate that you design ethically.

What will you build next?

If I had written this article in 1999 when winner-take-all business models were all the rage in the software industry, I’d sound like a nut. Or perhaps I’d just have an entry in /r/StallmanWasRight now. But I wouldn’t be singing in tune with a household understanding of software systems. These days, it’s a weekly (if not daily) occurrence to have even the mainstream media shout at us that we should be re-reading Stallman and Doctorow. From every sort of nontechnical user I hear the complaints. “Why can’t the police just check if the phones are doing something evil?” and “How can a company possibly keep my data without my permission?” To me, the answer is clear: one of the pillars is broken.

As the engineers of this disaster, let’s try a little harder when we pick our next jobs. Given the charges of this article, would you be happy to work at Slack today? Microsoft? Twitter? Facebook? Google? Amazon? Strava? Spotify? Medium? Uber? Go-Jek? Grab?

Under their current business models (and current ethics), I couldn’t work at any of them.

If Steve Yegge honestly believes that the big players have stopped innovating and the little guy is blazing a righteous new trail for the world’s users he might want to use the predictive function from Part One to anticipate just what sort of outcomes he’s a party to.

[1] Yes, WhatsApp released encryption based on the Signal Protocol in 2014. However, release to all platforms and an official announcement which put it in the public eye wasn’t until 2016.

[2] As feedback for this article, a friend suggested non-profits as a sustainable alternative to corporations. In the context of federation, where federation distributes responsibility of the service to more nodes of the network, what brand of single point of failure you choose is irrelevant: a corporation is a religion is a government is a university is a non-profit. All imagined entities share the fragility of being imaginary. Little strength is gained by choosing a better imaginary friend. Strength comes from diversification.

It’s worth remembering there’s no clear hierarchy to federation and distribution, either, but in general: more actors is preferable to fewer actors, trustworthy actors are preferable to bad actors, and a protocol which defines an evolving system architecture is preferable to one which hopes to get it all perfect the first time (even if it’s not the first time). There are systems which, initially, require centralization. It’s hard to imagine a federated Airbnb or TransferWise the first time around. But, whether in two years or in twenty, the design of TransferWise will be no more interesting or revolutionary than ride-share services are today. If the solution to the problem statement I want to easily and legally move rupees out of India online is still the monopoly of TransferWise in 20 years, we’ve spent 20 years wasting a lot of resources on a very boring problem.

[3] I will use “Free” and “open” interchangeably for most of the article. I’m picking my battles and I make no apologies.

[4] If you have the Skills Of An Artist and care to replace this with a more polished drawing, I will happily accept such donations.

Essay originally published on medium.com/@deobald (2019).